“You ask any cab driver in town where the best burger is, and they’d say Clown Alley — and they’d mean us,” San Francisco restaurateur Bill Pailhe told reporters in 1994. “But sometimes people went to the other one.”

Most cities can’t boast a late-night burger joint themed around the part of a circus tent where clowns don their makeup. But, for a time, San Francisco had two. The rivalry between the city’s two Clown Alleys, located 2 miles apart on either side of Russian Hill, lasted for three decades and ended with looming lawsuits and an earthquake.

It started in 1962 when larger-than-life North Beach business owner Enrico Banducci drove past an unusual looking gas station on the corner of Columbus and Jackson. “What a great hamburger stand that would make,” his passenger and friend Morgan Montague remarked.

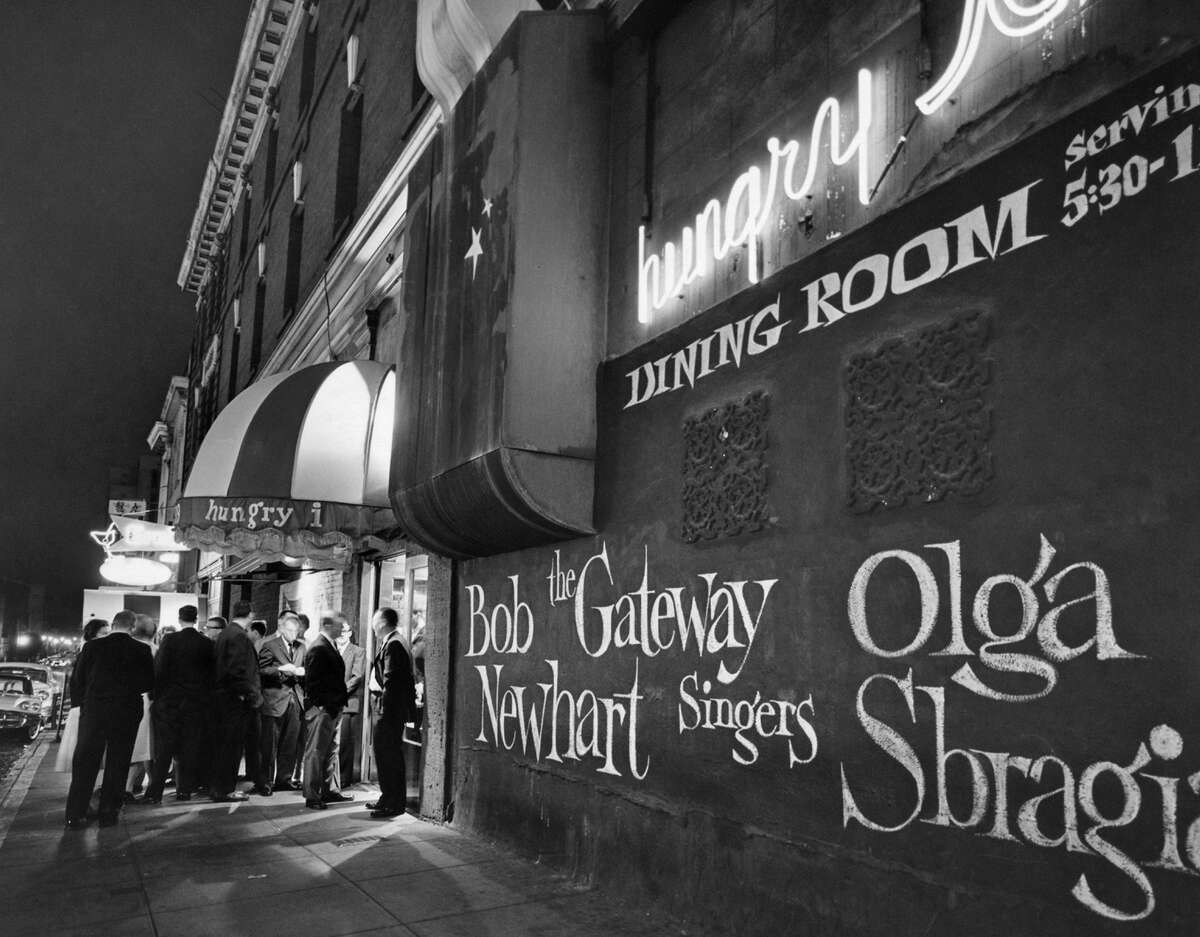

The colorful sign to Clown Alley in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood.

Thomas Hawk via Flickr CC 2.0Within a few months, Montague and Banducci opened the first Clown Alley hamburger stand at the same spot. The triangular cafe and outdoor patio, located on the edge of North Beach’s party scene, became a wildly popular late-night, post-cocktails hangout.

The shack was one of the only all-night eateries in the city, and within a year, the partners opened a second Clown Alley on the corner of Lombard and Divisadero.

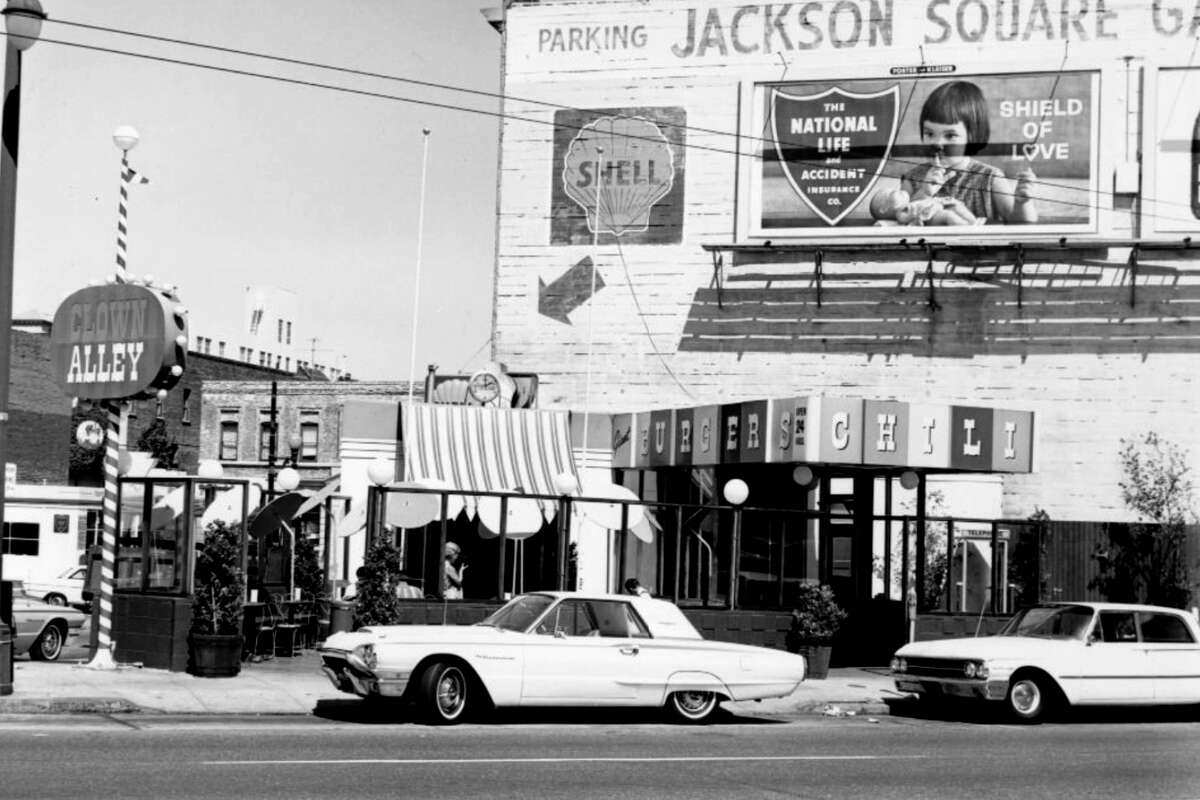

Banducci was no stranger to nightlife entrepreneurship, having turned the Hungry I nightclub in the basement of the since torn-down I-Hotel on Jackson Street into a nationally known hotspot. That club helped launch the careers of Woody Allen, Bill Cosby and Barbra Streisand before moving locations and closing in 1970. (The Hungry I strip club on Broadway, which closed in 2019, took the same name, but was never owned by Banducci.) The impresario also founded the legendary North Beach hang out Enrico’s on Broadway.

Outside of the Hungry I nightclub in San Francisco when Bob Newhart and the Gateway Singers were due to appear in the 1960s.

Pictorial Parade/Getty ImagesThe Columbus location of Clown Alley was managed by a man named Alfred Pailhe, and his son Bill started flipping burgers there at the age of 14.

Banducci, whom the Examiner once described as “the monster who devoured North Beach,” was by all accounts a volatile character.

“Enrico was eccentric. He could play concert violin but only when he was mad. But he was very bad in financial matters,” Bill Pailhe, now in his 70s, told SFGATE. “He had a plane he couldn’t fly and a pilot on 24-hour call. He had a sailboat in Sausalito that never left the dock.”

That volatility between the two partners ended their clown partnership almost as soon as it began, and by 1964, the Clown Alleys were two separate entities, and rivals, with Montague running the Lombard location and Banducci passing on ownership of the Columbus spot to Pailhe to settle some debts, Pailhe says. And not long after leaving college, Bill was running the place himself.

“I had someone paint this huge clown mural on the back wall. Everything had clowns on it,” Pailhe says.

Clown Alley, 42 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, circa 1964.

San Francisco Public Library

Clown Alley mural

Jane K. via Yelp

Clown Alley

Courtesy of Clown Alley

Clown Alley

Courtesy of Clown Alley

(Images via San Francisco Public Library & Courtesy of Clown Alley)

That mural was a sight to behold — at the forefront, a looming 6-foot-tall sad clown watched over diners.

“I didn’t know at the time so many people were afraid of them and didn’t like it,” he laughs. “But I never wanted to change the name.”

City columnists Herb Caen and Jeff Jarvis were regulars at the Columbus burger stand, which soon became a bona fide and beloved San Francisco institution.

“It was the best flame-broiled burger in town,” Pailhe says. “My father was great friends with Herb Caen, so we’d get some good publicity, too.”

Caen mentioned his favorite burger joint at least 30 times over the years, though the revered columnist did complain that the Alley’s “foot long” hot dog was only 10 inches in length.

Everyone raved about Clown Alley.

“People were lined up the street for flame grilled burgers,” Yelper Thomas B. wrote. “When you got about 10 people from the guy on the grill … you would shout out what you wanted.”

In the ’60s, with fast food on the rise, San Francisco socialite and man-about-town Peter Bakker told reporters he “abhorred” convenience dining, but made an exception for Clown Alley on Columbus.

The joint was even praised by esteemed city restaurant critic Jonathan Eddy. In a scathing review of San Francisco’s famed fine dining establishment, Jack’s, Eddy said that he was left so unfulfilled by the high end meal that he afterward walked down to trusty Clown Alley for a hamburger.

As one of the only 24-hour eateries in the city, much of the business came from the late-night scene at the famous club across the street.

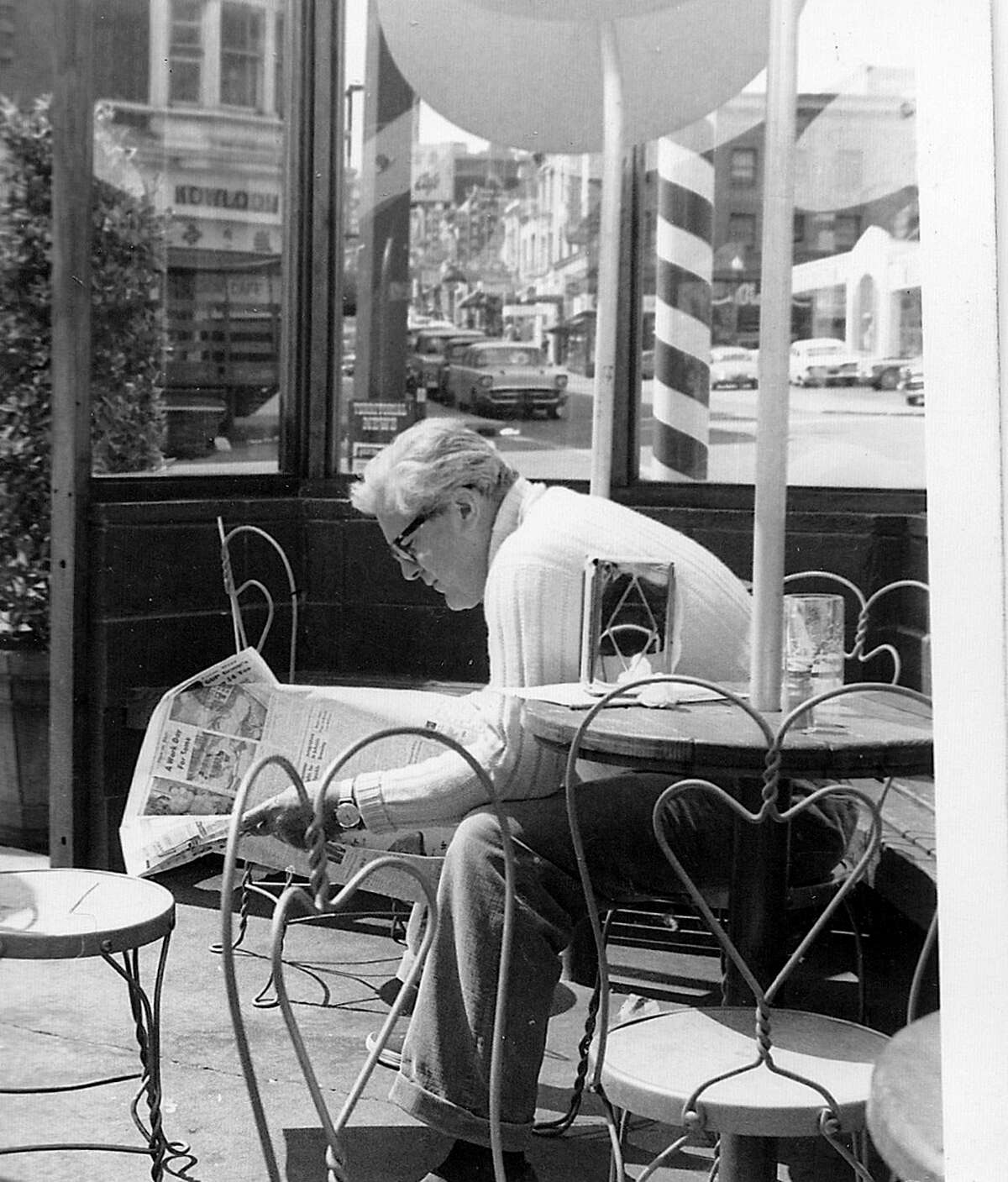

“The Hungry I was one of the most prominent nightclubs in all of the U.S. And when the show closed, everyone would come over to Clown Alley,” Pailhe says, adding that he remembers meeting Barbra Streisand before she was famous. “Bill Cosby used to send me Christmas presents,” he says. One story in the Examiner says that Streisand would occasionally even help in the kitchen. During the day, famous lawyer Melvin Belli would stop by with his three miniature greyhounds and read a paper, as others would nurse hangovers with a cheeseburger and coffee.

Well-known San Francisco attorney Melvin Belli at Clown Alley, circa 1964.

Gary Stevens via CC 2.0Business at 42 Columbus was good. “The rent was so low, the jukebox paid for it,” Pailhe says.

Meanwhile, Montague’s Lombard location had a less stellar reputation. One local described the burgers to the Examiner as “good … if you were starving.”

The ambience on Columbus was kitschy but cool, with its red vinyl stools, circular cartoon-like sign hovering over the glassy triangle building and sunny outdoor patio.

Across town, the Lombard location sported a garish interior, with neon tables and a patio that one reviewer described as “smoggy” due to the busy traffic peeling off the Golden Gate Bridge.

“Oversized thin patty that manages to be dry and greasy at the same time,” a Chronicle reporter wrote of the Lombard spot. “It has a long way to go. My fingers smelled like greasy hamburger for hours, even after I had washed my hands.” That review made sure to mention that the Columbus location was under different ownership.

Columbus Avenue and Washington Street in San Francisco in 1965.

Thomas Hawk via Flickr CC 2.0One of the few times the Lombard restaurant got a mention in the paper was when it was revealed that notorious San Francisco drug dealer Stephen Green used the Clown Alley’s pay phone to push cocaine. It made the news again when a man known as “Dr. Sex” was arrested there on rape charges. (In the Lombard Street location’s defense, there’s no one around today to speak for its reputation.)

“We couldn’t take the name away from them at that point,” Pailhe says. He even tried rebranding his restaurant as the “Original” Clown Alley to differentiate the restaurants, he says.

Despite its murky reputation, the Lombard Street restaurant somehow stayed busy for 30 years. (It also made an appearance in an episode of the “The Streets of San Francisco,” the TV show that shot Michael Douglas to fame.)

“Montague had the rights to use the name, I couldn’t change that. They lived off our good publicity,” Pailhe says. “Tourists thought it was the same place, but the quality wasn’t the same. It wasn’t run well. It wasn’t up to par.”

It was only after Montague’s death in 1992 that Pailhe was able to trademark sole use of the name, a turn of events that perhaps unsurprisingly led to the Lombard spot’s closure.

In a 1994 Examiner story announcing its demise, the paper described the relationship between the shacks as a “30-year-feud.” It was reported that Pailhe had threatened lawsuits.

The manager of a nearby Marina print store said it wasn’t the mediocre burgers or even the name, but the 1989 Loma Pietra earthquake that likely sealed the Lombard Street Clown Alley’s fate. “Since the quake you don’t see much foot traffic around here,” Patrick Wong told the paper. “Nobody walks down the street.”

A view of Original Buffalo Wings on the corner of Lombard Street and Divisadero Avenue, which replaced the second Clown Alley location in about 1994.

Image via Yelp user Luke CAfter its 1994 closure, the Lombard location became New Yorker’s Buffalo Wings — it’s still a popular wings spot today.

The Columbus Street restaurant’s heady days looked to be over in 1996 when it shuttered to become a seafood restaurant. On its last day, a line of customers ran around the block to sit on the red stools for the last time and quaff milkshakes and burgers. One dramatic story in the paper led: “Clown Alley is dead,” and the new owners promised to keep the Clown Alley cheeseburger on the menu.

“I started coming here with my dad when I was 13, and my wife and I came here on our first date,” a regular told the Chronicle. “I’m a burger expert, and these are the best in town.”

Another report noted some graffiti in the bathroom that read “Clown Alley Will Live 4ever.” The daubings were maybe fated — just two years later, the seafood shack closed and Clown Alley was resurrected by Pailhe. It served burgers for another 11 years.

Clown Alley

Courtesy of Clown Alley

Clown Alley

Courtesy of Clown Alley

(Images courtesy of Clown Alley)

Clown Alley finally closed its doors for the last time in 2009, when it became tapas restaurant Bask. A few years after its closure, Facebook page Lost San Francisco posted a cool 1964 black-and-white photo of the restaurant under which veterans of the swinging ’60s San Francisco scene shared memories of Clown Alley.

“There was nothing like a big fat chili cheese burger at the Clown Alley after hours back in the day,” Kraig Kilby wrote.

“Been there many times after shows performing at The Purple Onion,” folk singer Chuck Cline commented. “Awesome burgers and shakes.”

Bask pulled down the clowns, put a roof over the patio, and saw good business at 42 Columbus until this year when, like so many San Francisco businesses of late, it announced its closure.

Sadly the vacancy doesn’t mean there will be room for even one Clown Alley in the future. Vietnamese restaurant Sai’s, currently located a block away on Washington, will be moving into the famous place later this year.

More than 60 years since he started flipping burgers at the alley, Pailhe has very fond memories of Clown Alley’s heyday.

“To this day I’ll run into people and happen to mention Clown Alley, and they’ll say, ‘Oh God, we used to go there after going to town to party,’” Pailhe says. “‘We’d always stop there on the way home.’”