Within months of the Pearl Harbor bombing on Dec. 7, 1941, the United States, in cooperation with Canadian authorities, set out to build a highway from British Columbia to Alaska, then a territory and viewed as vulnerable to attack by Japan. The original 1,685-mile road took more than 10,000 soldiers less than nine months to complete.

An upgraded version opened in 1948 and has been continually resurfaced and rerouted; It now measures just shy of 1,400 miles from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Delta Junction in Alaska, according to “The Milepost,” a guidebook to the drive.

The highway formed the heart of a family road trip I took last September from Alaska to Idaho, passing through the Yukon, British Columbia and Alberta, in Canada, along the way.

Relying on Google Maps won’t get you far on this drive, where cellphone service is sparse. In preparation, my son found a 1972 road map of western Canada and eastern Alaska that has remained fairly accurate.

The route, which takes motorists through some of the most stunning landscapes in North America, lends itself to a budget trip. We spent about $300 on fuel for the whole trip in a medium-size SUV. We often camped and ate picnic meals, starting in coastal Valdez, Alaska, where we overnighted on a 32-foot powerboat listed on Airbnb ($68 a night) with a great blue heron and a harbor seal as neighbors.

May and September, the start and end of the high-season months for traffic along this route, are also good times to see wildlife that is often pushed to lower elevations by snow.

Heading east on the Alaska Highway toward the Yukon village of Haines Junction.

(Andrew Strain via The New York Times)

Lessons in patience

From Valdez, we made our way to Wrangell-St. Elias National Park & Preserve (free), the largest U.S. national park, and then joined the Alaska Highway at Tok, a small town about 90 miles from the Canadian border that plays a large role in servicing sparsely populated eastern Alaska with its grocery stores, gas stations and restaurants.

We planned to drive deep into the Yukon on Day 1, but even with just 10 vehicles ahead at the border checkpoint, it took two hours to reach the lone agent, who asked us a few questions — mostly concerning firearms and hunting — and sent us on our way.

It was the first slowdown of many caused by stretches of unsealed road, construction detours and spots where the blacktop had pitched above frozen ground.

Kluane National Park and Reserve is home to 19,551-foot Mount Logan, the highest mountain in Canada, and more than 2,000 glaciers.

(Pete O’Hara and Jenna Dixon via The New York Times)

Yukon wilderness

Nearly 600 miles of the Alaska Highway traverse the Yukon.

From the border, the road travels southeast, passing yawning valleys with snaking streams and long glacier-fed lakes en route to Kluane National Park and Reserve, home to 19,551-foot Mount Logan, the highest mountain in Canada, and more than 2,000 glaciers. It, along with neighboring Wrangell-St. Elias and other parks, forms a UNESCO World Heritage site that enshrines the largest ice fields outside of the polar caps.

“This is how the Rockies would have looked years and years ago,” said Fitz McGoey, the visitor experience product development officer for the park, about 80 percent of which is covered by snow and ice.

Losing daylight, we opted for the first campground we could find north of the park. Quiet Lake Creek (20 Canadian dollars, or about $15, a night) offered riverside camping where we made quesadillas over a fire and fell asleep to the sound of a hooting owl while clutching cans of bear spray.

Musicians performing at the Fireweed Community Market, in Whitehorse, the Yukon’s capital.

(Cathie Archbould via The New York Times)

City break

After days of driving and camping, and one excellent reindeer hot dog from a gas station in Haines Junction, we stopped in Whitehorse, the capital of the Yukon and the only major city on the highway, which was on the 52 Places to Go in 2024 list as a destination for northern lights tourism.

Across the 350 forested acres of the nearby Yukon Wildlife Preserve, a three-mile trail linked the habitats of 12 tundra species, including thinhorn sheep, arctic fox and Canadian lynx (admission CA$19).

Arctic and red foxes, above, are among the animals found in the Yukon Wildlife Preserve.

(Seth Bartusek via The New York Times)

Checking into the Raven Inn (CA$284), we explored Whitehorse’s walkable downtown and splurged on dinner at Belly of the Bison (bison Bolognese, CA$34). Afterward, our server directed us to the ’98 Hotel lounge for “a real taste of Whitehorse.”

It was open-mic night in the bar, which was decorated in animal skins and antique rifles, and free mugs of Molson beer arrived whenever someone rang the bell above the bar to buy the house a round.

The emcee encouraged reluctant talent by reminding the crowd, “There is no tomorrow if you don’t live today.”

Signpost Forest, in Watson Lake, Yukon, is a forest of poles displaying road signs and license plates posted by motorists.

(Mehak Khan via The New York Times)

Yukon kitsch

For the most part, the Alaska Highway is free of roadside kitsch with one enormously engaging exception: Signpost Forest in Watson Lake, Yukon (free).

Roughly 270 miles southeast of Whitehorse, a forest of poles displays innumerable road signs posted by motorists since 1942 when a homesick American soldier named Carl K. Lindley erected a sign with the mileage to his hometown, Danville, Ill.

Now license plates and tributes constructed of everything from flip-flops to a toilet seat compete with the signage.

“We call it the largest public display of stolen property in North America,” said Chris Irvin, the mayor of Watson Lake, in a phone interview, who estimated there are about a million signs in the forest.

Caribou on a stretch of the Alaska Highway in British Columbia.

(Destination BC/Andrew Strain via The New York Times)

In British Columbia, springs and safaris

In Alaska and the Yukon, we’d spotted bear and moose. But the wildlife in northern British Columbia, which we entered shortly after the Sign Post Forest, felt like a safari.

We saw black bears emerging from the woods and frequently stopped to view caribou grazing or herds of wood bison on the highway shoulder. A family of thinhorn sheep licking salt from the road nearly collided with our vehicle, their hooves skittering on the pavement.

Reassuringly, our next stop, Liard River Hot Springs Provincial Park, offered camping behind an electric bear fence (CA$26 a night). Campers have unlimited access to the springs, reached via a boardwalk — the original was built in 1942 by American forces — over a warm-water swamp and a boreal forest so unusual in nurturing species like orchids that it was originally named Tropical Valley.

With mossy banks, rubble bottoms and temperatures that ranged from about 108 to 126 degrees, the park’s natural pools stayed open around the clock, and we found solitude both at night while stargazing and the next morning in the fog of dawn.

Elaine Glusac and her family at the Alaska Highway’s Mile Zero marker in Dawson Creek, British Columbia.

(Seth Bartusek via The New York Times)

Mile Zero

The highway flattens as it nears its origin in Dawson Creek, a British Columbia town of 500 that grew virtually overnight to roughly 10,000 when highway construction began. Black-and-white photos of servicemen working on the road, sitting atop a truck mired in mud and bathing in a river filled the hallways at our hotel, the no-frills George Dawson Inn (CA$174, including breakfast).

The highway’s much-photographed Mile Zero marker neighbors a former grain elevator that has been restored as the Dawson Creek Art Gallery (free).

The gallery’s back stairway exhibits a collection of photos, letters and tributes called “The Road.” It included this anecdote: When the Indigenous people of Canada’s north questioned the speed of the road’s construction, they were told about Hitler’s plan for world domination, to which one replied, “What’s he want all that land for? He will surely die someday like everyone else.”

Alberta’s parks

From Mile Zero, the most direct route to the Lower 48 crosses into Alberta and transits two marquee attractions of the Canadian Rockies: Jasper National Park and neighboring Banff National Park.

In view of rising mountains, immense river valleys and herds of elk, we drove 280 miles, primarily on Highway 40, to Jasper National Park (CA$22 per family or group). Its main road follows the glacial blue Athabasca River to the town of Jasper, where we checked into HI Jasper hostel (CA$306 for a four-bed private room).

Rising early, we beat the tour buses to the park’s Maligne Canyon to peer into a river-carved chasm, following the flow from a cliff-top trail that descended with the river to rapids and pools.

Bow Lake, just off the Icefields Parkway, which connects the towns of Jasper and Banff in Canada.

(Josh Segeleski via The New York Times)

Connecting Jasper and Banff over roughly 145 miles, the Icefields Parkway offered spectacular views of waterfalls and peaks winking in and out of the clouds. We picnicked on the rocky shores of the Athabasca and skipped tourism developments like the glass Columbia Icefield Skywalk, where admission starts at CA$41.

A double rainbow arched across Highway 93 as we entered Banff, the popular Canadian mountain town. We stayed just outside the busy city center at the Juniper Hotel (CA$317) and used its free shuttle service to hit the town center for a round at Three Bears Brewery and Restaurant (pints CA$9) and stock up on picnic supplies at Wild Flour Bakery.

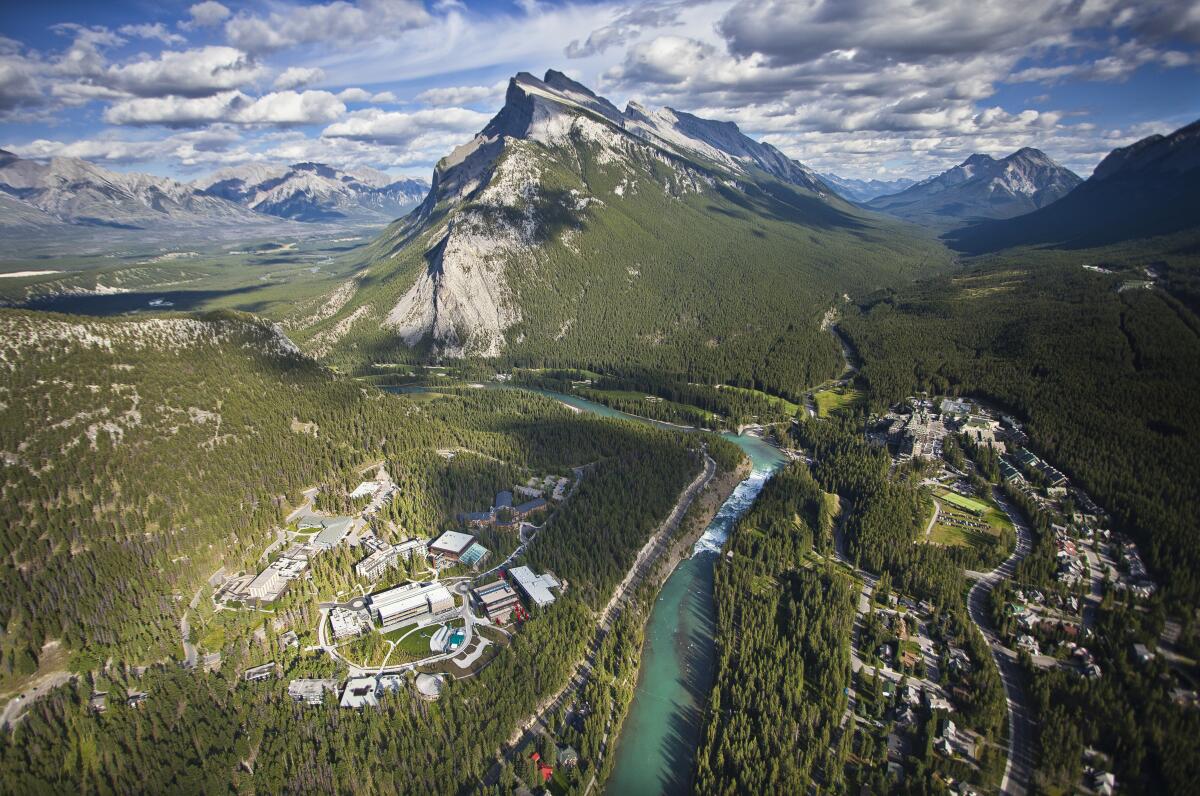

An aerial view of Banff, a resort town in Banff National Park, in Alberta.

(Paul Zizka via The New York Times)

A quiet alternative

On a sunny morning, as Banff flexed its magnetism, framing mountain views down seemingly every lane, we backtracked about 18 miles to rejoin Highway 93 as it takes a southwestern swing into Kootenay National Park (CA$22 per family or group).

In Kootenay, we had Marble Canyon, a 200-foot gorge with marble walls polished by a roaring river, to ourselves. Seven bridges allowed us to cross the narrow gap as ruby-crowned kinglets sang from the pines.

Marble Canyon is a marble-walled gorge in Canada’s Kootenay National Park.

(Elaine Glusac via The New York Times)

We found Kootenay’s crowds at Radium Hot Springs (CA$17.50). Surrounded by forested slopes, the large pool lacked the aura of a wilderness hot springs, but with family-friendly shallows and a stinging cold plunge, it was a great diversion.

Driving through Sinclair Canyon, near Radium Hot Springs, British Columbia.

(Kari Medig / KootenayRockies.com via The New York Times)

Last call

From Kootenay National Park, the U.S. border lies about 140 miles south on uncrowded roads that follow rivers and lakes, skirting the British Columbia ski town of Kimberley, where we spent our last night at its new boutique hotel the Larix (rooms from CA$155 dollars, including breakfast).

The tiny former lead-, silver- and zinc-mining town is now an outdoorsy destination with three golf courses, a downhill ski area and over 60 miles of bike trails. Restaurants and breweries in the pedestrian center included Hourglass, serving cocktails, charcuterie and cheese plates (from CA$22). “We do pack a lot into this little town,” said Breanna Fast, a co-owner.

Just over an hour from the border, Kimberley made a fitting finale to a trip so packed with sights that I never cracked the novel I brought.

Glusac writes for The New York Times.

The former mining town of Kimberley, British Columbia, is now an outdoorsy destination for skiers, snowboarders, bicyclists and hikers.

(Kari Medig / KootenayRockies.com via The New York Times)