“You may not have decided on a final destination,” Leonard continues, “but along the route you’ll stop at different ports of call. You must take control of your life and set a course in the direction you want to go. Otherwise, you are subject to unpredictable circumstances.”

That would be a good epigram to open a film looking back on the life and career of an artist, which “Flipside” is. But it turns out that Leonard, who died before enough footage was shot to finish such a film, is not the artist whose life is under the microscope. That would be the director, Chris Wilcha, a filmmaker who made a small splash in 2000 with the release of “The Target Shoots First,” a humorous memoir about the onetime philosophy major and aspiring documentarian’s struggle to maintain artistic integrity while working in the marketing department of the Columbia House Record Club.

After “Target,” Wilcha mostly supported himself as a director of television commercials, with stops along the way to collect an Emmy for directing the short-lived “This American Life” TV show, and for making a making-of documentary about Judd Apatow’s film “Funny People.” That behind-the-scenes film aired precisely once on Comedy Central, we’re told, before ending up as a DVD extra on the 2009 film’s home-entertainment release. Wilcha’s own life, it seems, is littered with abandoned and dead-end projects.

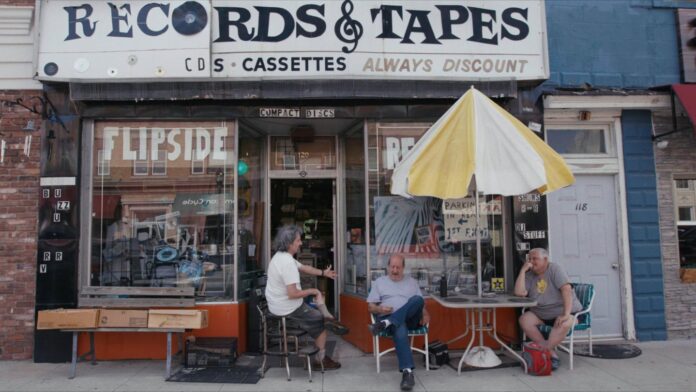

Ostensibly a documentary about the New Jersey record store where Wilcha worked as a teenager, “Flipside” (which takes its name from said emporium of vinyl) ultimately turns out — hilariously, bizarrely, brilliantly — to be about so much more than a now-foundering music store that at times it teeters on the verge of being as cluttered as its namesake. In addition to appearances by Leonard, Apatow and Ira Glass, “Flipside” includes interviews with Wilcha’s parents; writer/producer David Milch, creator of “Hill Street Blues,” “NYPD Blue” and “Deadwood,” now diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and the man who originally hired Wilcha to make that abortive movie about Leonard; writer Starlee Kine, who speaks about her own struggles with writer’s block; Wilcha’s documentary “hero,” Errol Morris; and, perhaps most serendipitously, Floyd Vivino, a.k.a. Uncle Floyd, the Pee-wee Herman-esque host of a cult New Jersey and New York cable TV show from 1974 to 1998. Vivino, name-checked in the David Bowie song “Slip Away,” pops up here as a surprise customer of Flipside, but his presence ends up being less comedic than poignant, even profound.

As overcrowded as it all sounds, “Flipside” never falls off the cliff into confusion or incoherence, thanks mainly to Wilcha’s superb grasp of his theme. The director’s wise and discursive narration, which worms its way from regret about life’s disappointments to gradual acceptance of the compromises we all make, ties together the film’s subject matter with the skill and vision of a novelist, weaving together threads about creativity; doing what one loves vs. what one must; the impulse to hold on to the past, ever at war with the need to let go and move on; growing up and growing old; finding purpose; selling records and selling out; and discovering a kind of bliss in the cracks between. (When Wilcha returns to his parents’ house — still filled with his old record albums and his father’s vast collection of soap taken from hotels — you may be overcome by both feelings of nostalgia and the burning desire to have a yard sale.)

Like some jazz, perhaps, the movie is a simultaneously melancholy and lyrical meditation on life that, in the end, belies Leonard’s opening admonishment about our ability to set our own course. In “Flipside,” at least, control over one’s destiny is an illusion.

The title is intended both literally and figuratively. On one level, “Flipside” is a love letter to a dying business, whose owner, Dan Dondiego, is described as more archivist than merchant, trapped in the amber and inertia of the past. (The failure of his business, which predates the opening of a second, successful record store, may not be due entirely to forces beyond Dondiego’s control.) On another level, “Flipside” is a poetic allusion to the B-sides of life: all the roads not taken and the one path — or the one ride — we all inevitably end up on, despite kidding ourselves that we’re at the helm.

Unrated. At the AFI Silver. Contains nothing objectionable. 96 minutes.