Dressed in outfits that recalled Philadelphia’s colonial days, they hid out in homes around modern-day Grays Ferry and Graduate Hospital, often waiting until the early morning hours to strike. Sometimes their targets were ships or stevedores. Other times they were well-to-do pedestrians. They occasionally broke into homes, carting off valuables or even fireproof safes to crack open for plunder.

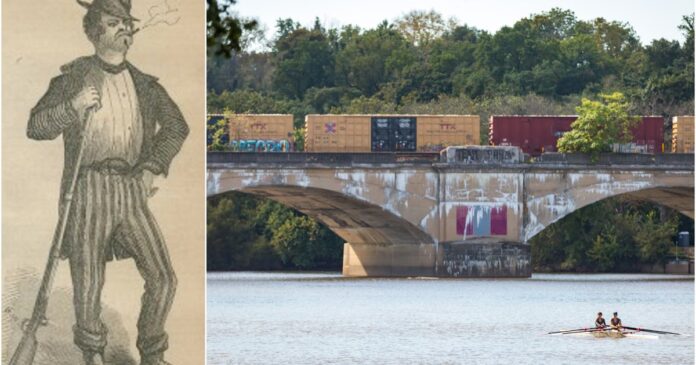

They were the Schuylkill Rangers, the Irish pirate gang of 19th century Philadelphia, and they were by all accounts “a horde of daring wretches and vagabonds.”

The Schuylkill Rangers first appear in newspaper records around 1848, a time when South Philly was plagued with gangs. As Ken Finkel, a history professor at Temple University, writes, lax police presence below South Street led to a surge in gang activity in the 1840s as at least 65 gangs attacked city residents with guns, bricks and slingshots. They marked territory by writing their colorful names — such as the Nighthawks, Gumballs or Vampyres — in chalk or charcoal across doors and fences.

According to “Publications of the Historical Society of Pottsville,” members of the Schuylkill Rangers “assumed the style of Colonial or Revolutionary wars,” and traveled in groups, carrying flintlock muskets and other weapons. They were primarily Irish immigrants who banded together shortly after the nativist riots of 1844 left two Irish Catholic churches and several homes burned. The Schuylkill Rangers often boarded boats along the eastern shore of their namesake river, brandishing weapons and demanding not just money but sometimes food and liquor. Stevedores or boatmen might also be attacked on their way to the river, by packs of “rangers” under the cover of darkness.

Sometimes the frustrated boat captains fought back, leaving the Schuylkill Rangers wounded in the hospital (from which at least one escaped). But they apparently never expected help from law enforcement. In 1849, the Public Ledger relayed the suggestion of a Rochester paper that “the United States authorities ought to take jurisdiction over the Schuylkill, so far as to dispatch thither a naval force to dislodge these land pirates, who do not seem to be worthy of the police.” The seafarers of the Schuylkill were on their own.

While the gangsters were most famous for sticking up boats, they also robbed homes and occasionally people on the street in broad daylight. A gangster known as “Limpy Clark” perpetuated one such incident on the afternoon of Aug. 13, 1876, against a well-regarded society man named L.P. Ashmead. As reported by The Philadelphia Times:

“Colonel Ashmead, accompanied by a lady relative, went out in the afternoon to sniff some fresh breeze on the Schuylkill. On the east end of the South street bridge a muscular young man made an attack on him. The Colonel took out his eyeglasses to secure a full comprehension of the situation, when the unknown man of muscle grabbed the golden goggles with one hand and with the other grasped for the (colonel’s) gold watch and chain. The scoundrel succeeded only in securing the gold chain, with a valuable locket attached thereto. Colonel Ashmead at once sounded the alarm and asked some fifty loafers, who were sunning themselves on the bridge, to aid him in capturing the robber, but not a single favorable response was made. Unwilling to be despoiled of his valuables, he followed the unknown single-handed, and in the course of time was joined by two policemen.”

The Schuylkill Rangers also committed crimes that were almost comically petty or downright bizarre. In 1870, a boy who liked to fish at Fairmount Park wrote to the Inquirer complaining that the “ruffians” broke and stole his friend’s net and swiped another kid’s haul of 17 fish. The Evening Telegraph, meanwhile, carried an 1867 report of gang member Jim Lynch’s drunken spree in which he “amused himself with a large knife, and went about doing mischief” in a slaughterhouse, stabbing already dead pigs.

The press paid close attention to the Rangers’ rise, writing numerous stories about not just gang activity but the Schuylkill Rangers’ most notorious leaders, who became minor sensations. There was Jimmy Logue, the prolific bank robber suspected of murdering his wife, and William Keating, the would-be priest turned highwayman and “general rough.” Perhaps the most covered was Jimmy Haggerty, a career criminal who once escaped police captivity at the courthouse and, in an earlier incident, was pardoned from a prison sentence on the condition that he leave Pennsylvania (he didn’t). When Haggerty was apprehended by authorities in 1870, the Inquirer wrote just two pithy lines: “Jimmy Haggerty has been caught. Good.”

Many different people have been credited with bringing down the Schuylkill Rangers, and ironically, several of them were Irish cops. They include Lt James Flaherty, of the 5th District, who came to America with his parents at the age of 9, and St. Clair Augustine Mulholland, a Civil War hero and the chief of police under Mayor Daniel Fox. It’s unclear when exactly either man broke up the gang, but by the 1880s, newspapers discussed the Schuylkill Rangers’ misdeeds in the past tense, like an unfortunate episode they had moved past. Members were apparently still active enough to be “very annoying” to the residents of Chester, according to a 1900 Inquirer report, but their glory days were long behind them.

With the exit of the Schuylkill Rangers, the river was safe again for boaters and rich men hoping to sniff some fresh breeze with their lady relatives. Or at least it was safe until it met a more modern foe, with stronger weapons than the gangsters’ old slungshots and knives — pollution.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.