On the evening of Sept. 14, 1861, about 1,500 people piled into the Continental Theater on Walnut Street to see an elaborate performance of William Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” complete with a large cast of young dancers eager to take part in the over-the-top production.

Among them were four sisters: Ruth, Abeona, Cecilia and Hannah Gale. The English performers, all under 23 years old, had toured the country before arriving in Philadelphia for the show. The sisters were accomplished dancers and had spent much of their young lives performing with theater troupes. As they prepared for the second act, they were unaware of the tragic scene that was about to unfold in front of them.

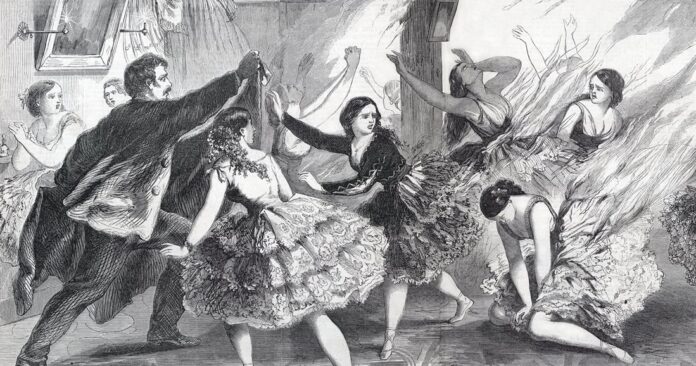

It is believed that one of the sisters was reaching for a costume when she came in contact with a gas jet that ignited her clothing. Her sisters and the other dancers attempted to extinguish the fire, but the blaze continued to spread among them.

William Wheatley, an actor who had leased and refurbished the Continental Theater in the weeks leading up to opening night, instructed the crowd to evacuate after he realized the severity of the fire. A dozen of the girls, including the Gale sisters, were trapped in the blaze. Some of them jumped from windows in an effort to escape.

The theater was burned to the ground, and nine of the dancers were killed, including all four Gale sisters. Wheatley, who was exonerated of responsibility for the fire, held funeral services for the dead dancers and paid for their burials at the Mount Moriah Cemetery in Southwest Philly.

Their grave marker, which has decayed and is no longer legible, garnered attention this spring when The Famous Grave Co., a pair of social media accounts that posts burial plots of historical figures from across the country, posted an image of the memorial to Instagram.

“I’d never heard of these girls,” said Gary Sweeney, the Philly resident behind The Famous Grave Co. “Since the volunteer group (tasked with the cemetery repair) has cleared a lot of the sections and made them visible, I’ve been back there several times. It was a big story at the time, especially since the city was in a depressed state from the onset of the Civil War, and the theater was a place people could go to escape reality. I don’t expect other people to know the story, but if they do come across something like that (the gravesite), it might prompt them to want to learn more.”

The Famous Grave Co., which Sweeney started in November 2021, has more than 15,000 followers on Instagram and 71,000 on TikTok. He has posted the resting places of artists like Bessie Smith, Marian Anderson, Whitney Houston, Bobby Rydell, Luther Vandross and Christina Grimmie, as well as notable people like Benjamin Franklin, Octavius Catto, Beau Biden and Catherine Sweeney, the wife of chocolatier Milton Hershey.

Despite the account’s name, not everyone Sweeney focuses on is famous. Some are crime victims or people he has come across with interesting life stories.

Sweeney’s relationship with the Mount Moriah Cemetery began in the 1990s, when he was a teenager reporting for a newspaper in Southwest Philly. At the time, Sweeney said, the cemetery was under negligent ownership and his work garnered the attention of state representatives and community members. After the ownership group left – shortly after he began reporting on the cemetery’s conditions – it fell into disrepair until the Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery began working to restore it.

As a self-described “taphophile,” a person who is interested in cemeteries and funerals, Sweeney wants to build a memorial plaque next to the Gale sisters’ gravesite for visitors to learn more about their story. After getting approval from the Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery, he began crowdfunding for the project on GoFundMe, earning more than $850 over the last few weeks. The plaque and its installation is estimated to cost $2,900.

Provided Image/Gary Sweeney

Provided Image/Gary Sweeney

The illustration above shows the memorial that Gary Sweeney, the man behind The Famous Grave Co. social media accounts, seeks to erect at the gravesite of the Gale sisters, who died in an 1861 theater fire in Philadelphia. Their marker is no longer legible.

“There’s a saying I’ve heard numerous times that after about two generations, you’re forgotten,” Sweeney said. “People who knew you in life would be gone at that point and if your great-grandchildren or great-great-grandchildren aren’t interested in knowing who you were, unless you’re famous, you’re forgotten.”

Peter Schmitz, an actor and adjunct theater professor at Temple University, said the story of the Gale sisters highlights the role that theater played during the Civil War. People were having a hard time, and, with Philadelphia being a major nexus of troops and transport for the Union Army, the city was filled with men looking for entertainment.

“The Philadelphia theater scene was booming, but it wasn’t at its most distinguished artistically,” Schmitz said. “The major stars left for Europe, but it was an exciting time to put on extravaganzas because people wanted entertainment in the midst of violent disruption.

“The show that the Gale sisters were in wasn’t popular with the stars of the 19th century because there were no flashy lead roles. London theater-makers at the time realized they could turn these into huge shows with ballerinas and have 50 to 100 women on stage at once for big choreographed numbers. The production of ‘The Tempest’ was a sort of knock-off of that, fanciful with a lot on display.”

Schmitz is the host of “Adventures in Theater History,” a podcast about the deep history of Philly theater. Along with Christopher Colucci, Schmitz delves into the scandals, riots and lawsuits associated with Philly theater dating back to the 18th century. In 2021, he dedicated a full episode to the prevalence of theater fires and how prevalent they once were.

The Continental Theater was was rebuilt after the 1861 fire, but it burned down three more times before it closed permanently. Now, the space at 807 Walnut St. is used as a parking lot. During its heyday, the theater had a more risqué reputation than a lot of other venues, with a focus on shows with dancing girls or burlesque, Schmitz said.

“The city responded to (the fire) in the way that they responded to other fires,” Schmitz said. “Fires were unfortunately very common and people just put up with it. It’s similar to how highway deaths were dealt with in the early days of the automobile. There had been other fires in Philadelphia and other major American cities, and people knew how to respond. In newspaper accounts of the time, any stories about a big fire would be followed up with a list of the recent fires that people could remember.”

In response to the fires, as with as other tragic events of the time, theater performers would host benefit shows to raise money for volunteer firefighters, charitable causes or for the families of the victims. Schmitz said a “heartening” aspect of the Gale sisters’ deaths is that they helped pave the way for theater people to institutionalize charities and organizations to serve the needs of performers at a time before unions and pension funds.

Once funded and installed, the memorial plaque for the Gale Sisters at Mount Moriah Cemetery would make for a fascinating stop on a history tour, Sweeney said.

“History is everywhere, it’s underneath everywhere you walk and I don’t believe in leaving things hidden or allowing them to be forgotten,” Sweeney said. “There’s probably millions of stories like this in Philadelphia alone, and they deserve to be remembered.”