It is a momentary idyll, the only idyll Jews in the Netherlands could allow themselves in the Nazi occupation during World War II. In short order, the men enter their home.

“Get our coats, please,” the father tells his daughter, disguising her escape as an errand. She leaves the room, exits the house through the kitchen, closes the garden gate behind her and runs into the darkness as her parents are taken away.

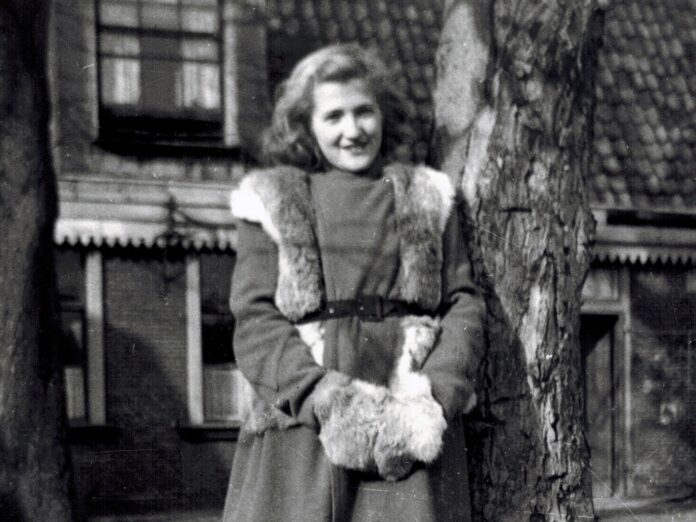

That young woman, the protagonist of the best-selling 1957 Dutch novel “Bitter Herbs,” bears striking resemblance to the book’s author, Marga Minco, a Holocaust survivor who became one of her country’s most distinguished women of letters and who died July 10 in Amsterdam at 103.

Ms. Minco was “often mentioned in the same breath in our country” with Anne Frank, said Victor Schiferli, a scholar at the Dutch Foundation for Literature, referring to the young diarist whose account of her time in an Amsterdam hideaway became one of the most widely read documents of the Holocaust.

“Bitter Herbs,” first published in Dutch as “Het Bittere Kruid” and dedicated to the author’s murdered family, was Ms. Minco’s debut novel. For generations it has been required reading in schools in the Netherlands. Readers around the world have come to know the book in translation, with the latest English version, by Jeannette K. Ringold, released in 2020.

Along with her subsequent novels and short stories, “Bitter Herbs” helped make Ms. Minco the “Dutch voice” in the canon of European literature that emerged from World War II, Mai Spijkers, the owner and director of Prometheus Books, the publisher of her later works, said in an interview.

Ms. Minco did not set out to describe the full horror of the concentration camps or the gas chambers or to capture the enormity of the Nazi murder of 6 million Jews.

Rather, she drew from her own experience to write in a way that “hints at, rather than spells out, sadness and suffering,” a reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement of London observed.

In one oft-cited passage of “Bitter Herbs,” Ms. Minco describes the conversation that ensues when the narrator’s father brings home a package of the Stars of David that Jews have been ordered to affix to their clothing.

“You ought to use orange thread for it,” not yellow, the narrator declares, confident that she has identified the best color for the job.

“If you ask me,” remarks her brother’s wife, “it would be better to use thread in the color of your coat.”

“It’ll look awful on my red jacket,” the narrator’s sister complains.

“I’ll leave it to you to figure out how to do it,” their father intervenes, oblivious as the others to the fate the stars portend.

With her exquisite austerity, “she makes tangible how unimaginable it was for a normal family to all of a sudden be persecuted and hunted down like the Jewish people were,” Schiferli said in an interview. “The quality of her literary work is very much the sparseness — the bare use of language,” he added. “Not one word is too much.”

Ringold, who has translated numerous works by Ms. Minco, was born in the Netherlands and survived the Holocaust as a child in hiding, losing her parents and much of the rest of her family. She was drawn to Ms. Minco’s writing after discovering a short story, “The Address,” also published in 1957 and later anthologized, that epitomized Ms. Minco’s understated power.

“‘The Address’ is about what happened to things instead of people,” Ringold said in an interview, “but of course the people are always there, right? You don’t see them because they’re dead.”

The story recounts the experience of a Holocaust survivor who shows up on the doorstep of an acquaintance to whom her mother had entrusted the family’s belongings before they were arrested.

At first, the acquaintance denies recognizing the woman.

“It was quite likely that I had pushed the wrong doorbell,” the survivor thinks, momentarily doubting herself. “The woman let go of the door and stepped aside. She was wearing a green hand-knit sweater. The wooden buttons were slightly faded from laundering. She saw that I was looking at her sweater and again hid partly behind the door. But now I knew that I was at the right address.”

“You knew my mother, didn’t you?” the survivor remarks.

Sent away, the survivor later returns to the address and is received by the acquaintance’s daughter, who invites her in for tea. She finds herself surrounded by objects she recognizes — her family’s menorah, their gold-edged tea pot, their tablecloth and teaspoons. The survivor abruptly leaves, hearing the clinking of silver as she walks away.

Like her character, Ms. Minco paid a visit after the war to the address where her mother had placed their family’s belongings in keeping. As in the story, the daughter invited Ms. Minco in and blithely discussed the lovely housewares all around, unaware of their provenance.

In real life, Ms. Minco allowed herself an action that her fictional protagonist did not take. When the daughter went into the kitchen to prepare tea, Ms. Minco secretly grabbed a handful of silver teaspoons to take home. “We still have them,” her daughter Jessica Voeten wrote in an email.

Sara Minco, the youngest of three children, was born in Ginneken en Bavel, near the Dutch city of Breda, on March 31, 1920. Her father was a traveling salesman, and her mother was a homemaker.

After attending a high school for girls, Ms. Minco became an apprentice reporter at a newspaper in Breda, the Bredasche Courant. She was fired after the German invasion in May 1940 because she was Jewish.

Ms. Minco and her family were forced from their home and relocated in Amsterdam, where the Nazis concentrated many Dutch Jews before deporting them to the camps. Her sister and brother-in-law were the first members of the family to be taken away.

Nazi collaborators in the Dutch police came to arrest Ms. Minco and her parents in April 1943. While Ms. Minco managed to escape, her parents were deported and murdered at Sobibor extermination camp. Her brother and sister-in-law also perished in the war. Fewer than 25 percent of Dutch Jews were alive at the end of the Holocaust, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

While in hiding, Ms. Minco bleached her hair to help conceal her identity and lived under the assumed name of Marga, which she used for the rest of her life.

She lived for a period with a farmer and then with another family before moving in with a group of artists, where she was joined by her boyfriend, Bert Voeten, a poet and later a translator of Shakespeare. They were married in 1945, after the war.

Bert Voeten died in 1992. Their daughters, Bettie Voeten and Jessica Voeten, both of Amsterdam, are Ms. Minco’s only immediate survivors. Jessica Voeten confirmed her mother’s death but did not cite a cause.

Ms. Minco explored the war and postwar years in books including “An Empty House” (1966), “The Fall” (1983) and “The Glass Bridge” (1986), as well as in her short stories. One of the last stories she wrote was about the postcards Jews threw from train cars en route to the camps.

At age 98, Ms. Minco received the P.C. Hooft Prize, one of the highest literary honors in the Netherlands.

“I would have preferred not to have had a reason to write ‘Bitter Herbs,’” she had said years earlier. “But the facts are there, as is the book. And what counts for me is that those to whom I dedicated the book will now perhaps live on, and not only in my memory.”