CHAPA DARA, Afghanistan — Sayed Wali Sajid spent years fighting American soldiers in the barren hills and fertile fields of the Pech River Valley, one of the deadliest theaters of the 20-year insurgency. But nothing confounded the Taliban commander, he said, like the new wave of foreigners who began showing up, one after another, in late 2021.

Once, Sajid spotted a foreigner hiking alone along a path where Islamic State extremists were known to kidnap outsiders. Another time, five men and women evaded Sajid’s soldiers in the dark to scour the mountain. The newcomers, Sajid recalled, were giddy, persistent, almost single-minded in their quest for something few locals believed held any value at all.

“The Chinese were unbelievable,” Sajid said, chuckling at the memory. “At first, they didn’t tell us what they wanted. But then I saw the excitement in their eyes and their eagerness, and that’s when I understood the word ‘lithium.’”

A decade earlier, the U.S. Defense Department, guided by the surveys of American government geologists, concluded that the vast wealth of lithium and other minerals buried in Afghanistan might be worth $1 trillion, more than enough to prop up the country’s fragile government. In a 2010 memo, the Pentagon’s Task Force for Business and Stability Operations, which examined Afghanistan’s development potential, dubbed the country the “Saudi Arabia of lithium.” A year later, the U.S. Geological Survey published a map showing the location of major deposits and highlighted the magnitude of the underground wealth, saying Afghanistan “could be considered as the world’s recognized future principal source of lithium.”

But now, in a great twist of modern Afghan history, it is the Taliban — which overthrew the U.S.-backed government two years ago — that is finally looking to exploit those vast lithium reserves, at a time when the soaring global popularity of electric vehicles is spurring an urgent need for the mineral, a vital ingredient in their batteries. By 2040, demand for lithium could rise 40-fold from 2020 levels, according to the International Energy Agency.

Afghanistan remains under intense international pressure — isolated politically and saddled with U.S. and multilateral sanctions because of human rights concerns, in particular the repression of women, and Taliban links to terrorism. The tremendous promise of lithium, however, could frustrate Western efforts to squeeze the Taliban into changing its extremist ways. And with the United States absent from Afghanistan, it is Chinese companies that are now aggressively positioning themselves to reap a windfall from lithium here — and, in doing so, further tighten China’s grasp on much of the global supply chain for EV minerals.

The surging demand for lithium is part of a worldwide scramble for a variety of metals used in the manufacture of EVs, widely considered crucial to the green-energy transition. But the mining and processing of minerals such as nickel, cobalt and manganese often come with unintended consequences — for instance, harm to workers, surrounding communities and the environment. In Afghanistan, those consequences look to be geopolitical: the potential enrichment of the largely shunned Taliban and another leg up for China in a fierce, strategic competition.

Around the time Kabul fell to the Taliban in August 2021, a boom shook the world’s lithium market. The mineral’s price skyrocketed eightfold from 2021 to 2022, attracting hundreds of Chinese mining entrepreneurs to Afghanistan.

In interviews, Taliban officials, Chinese entrepreneurs and their Afghan intermediaries described a frenzy reminiscent of a 19th-century gold rush. Globe-trotting Chinese traders packed into Kabul’s hotels, racing to source lithium in the hinterlands. Chinese executives filed into meetings with Taliban leaders, angling for exploration rights. In January, Taliban officials arrested a Chinese businessman for allegedly smuggling 1,000 tons of lithium ore from Konar province to China via Pakistan.

Clean cars, hidden toll

A series unearthing the unintended consequences of securing the metals needed to build and power electric vehicles

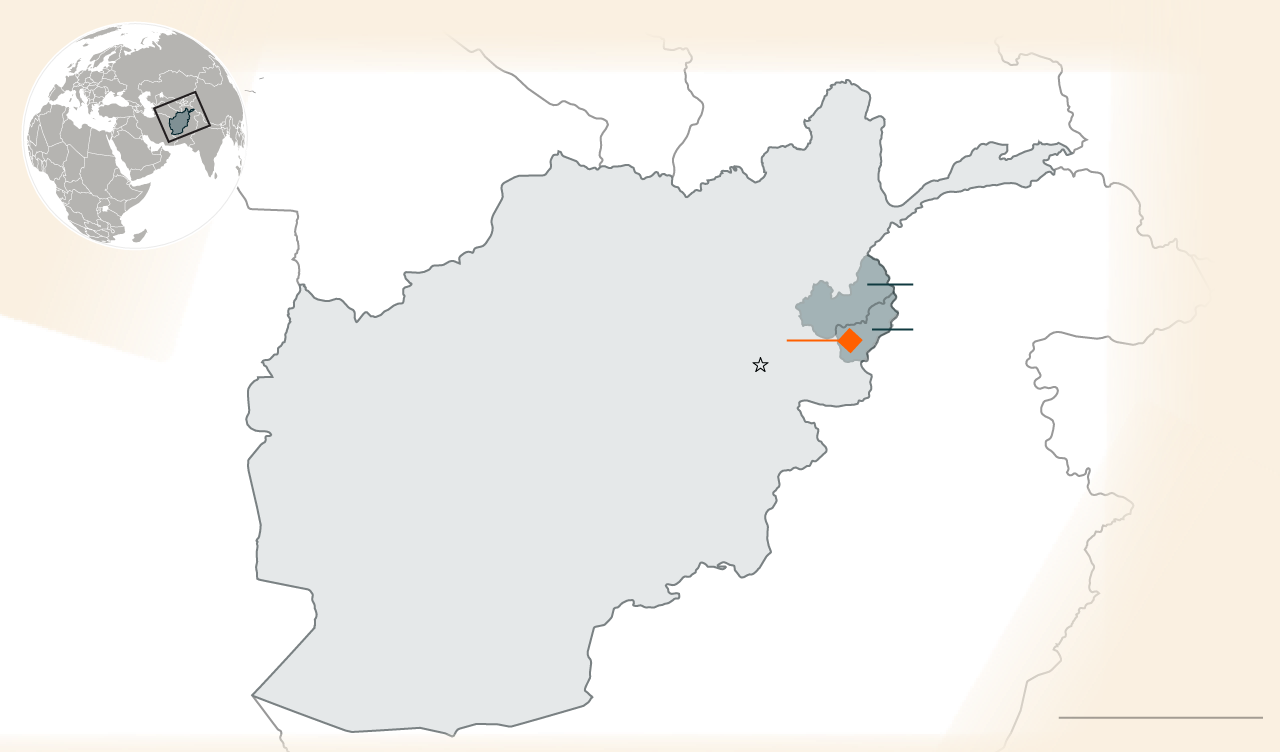

Taliban leaders have paused lithium mining and trading in recent months while they seek to negotiate a concession with a foreign firm, and the Chinese are seen as leading contenders. But even after a contract is awarded, extraction may not begin for years because of the challenge of bringing lithium to market, industry experts warn. There are no paved roads linking the craggy, mineral-rich mountains of northeast Afghanistan’s Konar and Nurestan provinces to the outside world, while abundant and more accessible reserves are found in countries such as Chile and Australia.

But what is certain, according to Afghans, Chinese and Americans alike, is that Afghanistan is in the midst of a sweeping transition after decades of war. And as long as the Taliban is ostracized by the West, they say, Afghanistan will drift by necessity, if not by choice, into the embrace of China.

“In an alternate universe, our projects could’ve been generating meaningful employment and tax revenue within years that would provide an economic base and empower the Afghan people to govern themselves,” said Paul A. Brinkley, the former U.S. deputy undersecretary of defense who oversaw the Task Force for Business and Stability Operations until he left in 2011 and the office disbanded.

Instead, Brinkley said, “we’ll have Chinese companies mining lithium to feed a supply chain that will ultimately sell it back to the West, all in a world where there’s simply not enough lithium.”

No one knew its value

Nesar Ahmad Safi trundled alongside the Pech River in a battered Toyota pickup, expounding on two forces that have long shaped life in Konar province: the war — and the mines.

“The Americans called it the Valley of Death,” he said, nodding toward the broad mouth of the Korengal Valley. Next to a bend in the rushing river were the tall gray walls of Nangalam military base, once the most remote outpost in the valley, now a vestige of the U.S. presence.

An hour past the abandoned base, the valley turned steep and rocky, and the snow-dusted mountains of adjacent Nurestan came into view. Safi pointed out dozens of small shafts that pierce the hillsides like dots of ink on brown parchment. Since antiquity, the mines have been a supplemental source of income for farming families, who extract precious stones such as quartz, tourmaline and kunzite, a glassy, purplish crystal, and sell them to the bazaars of Central and South Asia.

As they dig out high-quality kunzite, miners routinely discard heaps of milky rock. Locals called it “takhtapat” — waste kunzite. But geologists know it as spodumene, lithium-bearing ore. “No one knew the value of waste kunzite until Chinese businessmen started arriving,” said Safi, the former head of a village council who now works as a representative for local miners. “They were excited, then everybody got excited.”

Last year, Safi and local Afghans recalled, some Chinese traders bought as much ore as they could, sending brimming trucks down the valley’s bomb-cratered road. Other Chinese prospectors tested the rock with handheld spectrometers and voiced doubts that the lithium content was high enough to make industrial-scale mining viable, Safi said.

In the 1960s, Soviet geologists first reported significant lithium deposits in large crystal-laced rocks called pegmatites along the Hindu Kush range. After the U.S. invasion in 2001, U.S. Geological Survey teams working as part of the Pentagon task force ventured under Marine escort to southern Afghanistan’s salt-crusted lakes, where they found lithium content so high it rivaled the brine deposits of Chile and Argentina, some of the world’s biggest lithium producers. They also estimated, using aerial surveys, that Konar and Nurestan were rich in lithium-bearing rock, but the valleys were too dangerous to visit, said Christopher Wnuk, a former USGS geologist who participated in the Pentagon study. Even today, the exact size of Afghanistan’s lithium reserves remains undetermined.

“As a geologist, I have never seen anything like Afghanistan,” said Wnuk, who now works on private-sector mining projects in Asia and Africa. “It may very well be the most mineralized place on earth. But the basic geologic work just hasn’t been done.”

Even if Afghanistan’s mountains prove to hold high-quality lithium, the mines will be cost-efficient only if new roads, railways, ore-processing plants and power plants are built around them.

Not a problem, say China’s strategic thinkers.

“Afghanistan lacks an industrial base, [but] they have great mineral resources, and no Westerners can compete with the Chinese when it comes to building infrastructure and tolerating hardship,” said Zhou Bo, a retired People’s Liberation Army senior colonel who is now an international security expert at Tsinghua University.

In a rare interview, Shahabuddin Delawar, Afghanistan’s minister of mines and a senior Taliban leader, told Washington Post journalists that just 24 hours earlier, representatives of a Chinese company had been in his office presenting the details of a $10 billion bid that included pledges to build a lithium ore processing plant and battery factories in Afghanistan, upgrade long-neglected mountain roads and create tens of thousands of local jobs. His ministry identified the Chinese company as Gochin.

Delawar did not detail the timeline for awarding any mining concessions. He said a commission of senior Taliban officials led by Abdul Ghani Baradar, the deputy prime minister for economic affairs, “will weigh whatever good proposals we receive,” adding that the government would welcome Western and even U.S. bidders if sanctions were dropped. U.S. sanctions currently prohibit all transactions with the Taliban, with exceptions for humanitarian aid.

“We always said if the United States takes its soldiers and killing machines out of Afghanistan, it too could invest here,” he said. “The demand for oil is decreasing, but the demand for lithium is only going up. We have 2.5 million tons in Nurestan alone. Extract it, and Afghanistan can be one of the richest countries in the world.”

By 2030, when about 60 percent of all cars in China, Europe and the United States will be electric, the world is expected to face a lithium shortfall, said Henry Sanderson, executive editor of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence and the author of “Volt Rush: The Winners and Losers in the Race to Go Green.”

“China’s lithium sector is in a really enviable position: They dominate the processing, they’ve got the battery materials and factories, but that whole supply chain goes defunct if you don’t have raw material to feed the industrial machine,” Sanderson said. “That’s why they’re going to Afghanistan. They need to secure as much as they can.”

The Chinese gold rush

The first message that greets every passenger who walks out of Kabul’s international airport isn’t in English or Dari. It’s written in giant Chinese characters.

“The Belt and Road Initiative is the bridge spanning China and Afghanistan,” reads a massive billboard facing the terminal, referring to China’s global infrastructure program. “Welcome to China Town. Incubate in an industrial park. Let your investments take root.”

The billboard was erected by Yu Minghui, a fast-talking entrepreneur who hails from a village near the famous Shaolin Temple in China’s Henan province and first came to Kabul in April 2002, shortly after the U.S.-led invasion. He was 30 years old then, he said, and arrived with little more than a basic knowledge of Persian and searing ambition.

Today, Yu co-owns Afghanistan’s first steel mill and has permits for a 500-acre industrial park outside Kabul. The China Town project he advertises at the airport is a 10-story tower that Yu sees as a kind of Chinese chamber of commerce and showroom for imported goods. It sells power tools, diesel generators and even office tables that Chinese companies might need once they enter Afghanistan and start mining. In his office at China Town, Yu showcases chunks of Afghan lapis lazuli and lithium — along with his political savvy. In one framed picture, he’s striding alongside former Afghan president Ashraf Ghani’s brother Hashmat. In a more recent photo, Yu poses with a turbaned man who helped overthrow Ghani: the Taliban’s current commerce minister, Haji Nooruddin Azizi.

In late 2021, Yu recalled, he saw an influx of Chinese seeking opportunities in Afghanistan’s postwar vacuum, just as he did 20 years earlier. Within months, according to Yu and other Chinese residents, more than 300 of their compatriots had descended on Kabul. Some carried passports from Pakistan, Sierra Leone or other countries where they had immigrated to mine. Others showed up carrying a few packs of instant noodles in their backpacks, “wanting to get into the battery business,” Yu recalled.

“It felt like every Chinese wanted to come,” said Wang Quan, who has been mining gold in Afghanistan since 2017. “There were articles on the internet about how the Russians and Americans always said there was lithium here. At that time, lithium prices were truly amazing.”

Many Chinese packed into the downtown Guiyuan Hotel, which had a buzzing hot pot restaurant on the ninth floor. Yu Xiaozhang, the Chinese owner of a Kabul guesthouse, said she had three mah-jongg tables running round-the-clock in her basement. The boom even benefited the community of about 100 Afghan interpreters in Kabul who speak fluent Mandarin, thanks to the Chinese government-run Confucius Institute at Kabul University. They were enlisted to help arrange lithium purchases in Konar.

Then, late last year, the Guiyuan Hotel was struck by a bombing, which injured dozens. The Islamic State, which has targeted Chinese in Afghanistan, asserted responsibility. The attack raised new concerns about the safety of foreign businesspeople, adding to wider worries over the country’s investment climate. Soon after, the Afghan government imposed what it said was a temporary ban on private lithium sales while negotiating with mining companies and crafting new laws to regulate what had become a frenzied free-for-all.

Raffaello Pantucci, an expert on Chinese-Central Asian relations at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said the large-scale Chinese investment that the Taliban seeks may not be imminent, or transformative. In 2007, Afghanistan granted a $3 billion, 30-year lease on the Mes Aynak copper mine to the state-owned China Metallurgical Group Corp., yet little work has been done so far.

“The big Chinese companies are still very cautious,” Pantucci said. “If anything, China-Afghan economic relations will be driven not by the state, but by small private actors on the ground, just having a go.”

These days, a small, dedicated group of Chinese miners is still in Kabul waiting for the lithium trade to resume.

One of them is Yue, a gruff, chain-smoking native of Manchuria who has mined in Pakistan, Russia and Indonesia. He came to Afghanistan in late 2021 and plans to stay, he explained, because the Taliban is working hard to ensure foreigners’ security and even assigned him his own bodyguards. Afghanistan’s mineral potential is too great to walk away from, he added.

“After this many years of conflict, Afghanistan’s resources are untouched,” said Yue, who did not give his first name. “No mining licenses have really been given. There’s no place like it on Earth.”

Yue spends most days playing mah-jongg at a guesthouse, which serves Lanzhou beef noodles prepared by Afghan cooks. He’s still holding meetings with prospective investors. But mostly, he’s killing time until mining begins again.

“It won’t be frozen forever,” he said one afternoon in the courtyard of his home. “I’m happy to wait.”

The view from behind a glacier

In the inky underground darkness, a miner pressed his diesel-powered drill against the hard earth, caking everything — hair, clothes, lips — in a layer of fine white dust. Another stooped to fill a handcart with rocks, then pushed it 70 yards along the watery shaft, back into the light.

Hussain Wafamel squatted outside, where he examined the haul.

He held up a streaky, green stone: tourmaline, the kind of gemstone he and his men were seeking. Then he picked up a white rock — takhtapat, lithium ore — and chucked it over his shoulder, sighing with regret.

Last year, after Chinese buyers first arrived, the price of lithium ore was driven up to about 50 cents a kilogram, providing a windfall, Wafamel said. It was a shame that the Taliban had cracked down on the trade, he said, because the mountains here in Nurestan were full of the stuff.

“We have an entire mine of pure takhtapat,” said Wafamel, a squat and muscular former Afghan special forces soldier who mines with six men from his old unit. “We could be extracting a ton of it a day if it weren’t banned. Instead, we have to leave it.”

In some ways, the remote mine where Wafamel and his men toil day and night captures the practical challenges — and the dreams of progress — that lie in Afghanistan’s lithium wealth. His mine in the Parun Valley is hidden behind a glacier, high above the Pech River at an elevation of 12,000 feet. Outside his mine, in a cramped clearing overlooking a sheer drop, Wafamel complained about his fickle generator and his shoddy drill bits, the need to transport everything by donkey and the never-ending struggle to make ends meet.

Until two years ago, Wafamel and his team were each making $280 a month in the Afghan army, he said. They lost their jobs when the government fell. In a poor valley ringed by pine-covered mountains, where farming barely yielded enough food to keep families alive, the only option was to go to the mountains. So the men largely taught themselves what types of rock held rich veins, how to set sachets of ammonia explosives and where to drill.

“We want a bigger team and proper equipment, someone to show me how to use this,” Wafamel said, banging an oil-stained machine. “I’d be desperate for a foreign company to come.”

In recent weeks, Wafamel said, he has pleaded with government officials to allow lithium mining to resume. He said he was encouraged by their response that a deal may be signed with a foreign company, possibly this year, and optimistic that peace would engender investment. “If a villager can walk to the next province without trouble,” he said, “why wouldn’t foreigners want to invest here?”

A half-day’s drive down the mountain, not too far from the Valley of Death, Sajid, the 38-year-old Taliban commander who serves as governor of lithium-rich Chapa Dara district, was even more bullish.

Eighteen months ago, Sajid was flustered by the influx of Chinese prospectors. But these days, Sajid said, he’s “desperate” for them to return and bring jobs for locals and new infrastructure. Sitting in his compound with two captured American Humvees in the parking lot, Sajid said he was hearing promising whispers. A friend, a fellow Taliban governor, recently learned from senior officials in Kabul that a deal may be signed with Chinese investors in just a few months.

Sajid was already counting on a new asphalt road in his district. He was looking forward to new bridges.

And he relished the prospect of America losing again in his remote corner of the Hindu Kush, this time in a contest over minerals. “Sometimes I’m happy America sanctioned Afghanistan because American companies can’t invest in our lithium,” he said. “Actually, I believe it is the revenge of God.”

Mirwais Mohammadi in Chapa Dara, Pei-Lin Wu in Taipei, Taiwan, and Rick Noack in Paris contributed to this report.