The novels — with their wisdom-seeking, devotion to nature, vibrant family antics, old-fashioned storytelling, and enthusiastic use of vernacular, puns, exclamations and italics — had fervent fans, and fit on a shelf with a motley, crowd-pleasing, very American crew that includes Mark Twain, Edward Abbey, Norman Maclean and John Irving. (For the reason of energetic typography, you might throw in Tom Wolfe, too.) They left his readers wanting more.

But of all the things that have happened since 1992, a new novel from Duncan had not been one of them, until now. Little, Brown will publish “Sun House,” the author’s longest and most nakedly spiritual and earnest novel, on Tuesday.

Here I momentarily lift the impersonal scrim that journalists normally drape over this type of dispatch. I was barely 19 when I read, and fell deeply in love with, “The Brothers K.” My relationship to that 19-year-old self is a rapidly moving target these days, but I’ve spent the past 31 years as one of those readers eagerly awaiting news of Duncan’s next fictional act. (Three collections of acclaimed essays have appeared in the meantime.) Hints would emerge from time to time. For a while, the brief biography at the end of his nonfiction pieces would mention that he was working on a novel called “Nijinsky Hosts Saturday Night Live.”

Nijinsky never showed. Then came mention of a novel that would combine “his love for Asian wisdom traditions and the land and people of the American West.” In more recent years, that novel was named “Sun House,” and since 2016 it seemed that its publication might be imminent. Visiting Duncan in Missoula, where he has lived for the past 30 years, to talk about the book’s gestation felt like the opportunity for a long-desired pilgrimage.

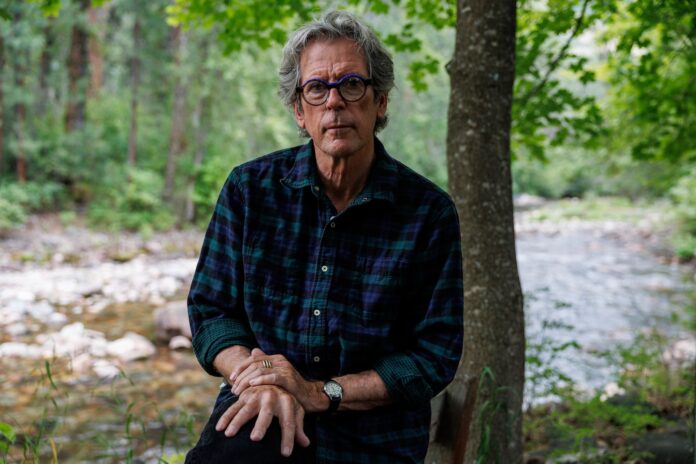

We first met in the townhouse he recently moved into beside Rattlesnake Creek — which got its name, Duncan promised, only from the shape of its course. The home is a five-minute drive north from the heart of this meadow- and mountain-ringed city, where the last evidence of daylight is still in the sky at 10 p.m. in mid-July.

Duncan, 71, was patient with questions, perhaps slightly reworded each time, that boiled down to: What took so long?

“I’m just a slow writer, and a huge reason for that is that I overwrite, so it’s more work for me to clean it up,” he said. “It doesn’t come to me in a succinct form. It comes to me in these big things I can grab hold of, but I know even while I’m dashing them down that they’re going to need a lot more work.”

He redrafted the table of contents for “Sun House” — his “main tool,” he said, for mapping out a novel as he writes it — more than 100 times.

“I’m just trying to keep the reader with me,” he said. “It’s like walking the Camino in Spain. It’s a long spiritual journey, and you’re making friends with people you’ve never met, the way people on the Camino just follow each other for 100 miles or so. That kind of a feeling.”

But talking to Duncan, it also becomes clear that he might simply view the passage of time — and how long it might take to, say, write a book — differently than the average person. More than once, he stopped short when he was about to name someone who has had a profound influence on his soul. (“Spiritual secrecy is the protector of spiritual integrity,” he said, citing Thomas Merton.) He felt more comfortable naming posthumous inspirations. To get a sense of just how posthumous, he named Zen master Eihei Dogen as someone he can safely discuss. Dogen died in 1253.

It’s as easy to summarize “Sun House” as you might imagine of a nearly 800-page novel that took 16 years to finish, with a plot that spans decades and follows the intersections of a dozen or so major characters, most of whom are initially unrelated. The people we meet earliest are Jamey, an actor who for many years recklessly endangers himself on his birthday because it also happens to be the day his mother died, when he turned 5; and Risa, a young woman who falls in love with Sanskrit and the ancient truths it holds. Soon after comes TJ McGraff, a budding restaurateur and ex-Jesuit novice, and his brother, Jervis, who, after he nearly dies from a violent assault, becomes a “voluntarily impoverished street mystic.” A folk singer named Lorilee (Lore); a mountain-range lover named Grady; and a woman named Gladys who helps Grady love them better. And more. It’s a crowd. And eventually many of them convene in western Montana, where they take on a multinational corporation to acquire 4,000 acres of land for communal living.

Jervis is permanently disfigured from his attack (scarring, nerve damage, loss of sight in one eye and the reduction of his voice to a papery whisper), but the very bright silver lining of its aftermath is that it puts him in direct touch with something he refers to as Ocean, the “shoreless” feeling of the universe’s plenitude. He cites Father Zosima from Dostoevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov” as another proponent of the concept (“all is like an ocean, all is flowing and blending”). Jervis can’t influence this force, but he can help put other people in touch with it, and he wanders the streets of Portland, Ore., full time doing that. (“I don’t even know what I’m saying,” Jervis says of his interactions with people. “They’re playing ping-pong with Ocean. I’m just the paddle.”) He also espouses a “street faith” that he calls Dumpster Catholicism, which values all the “misunderstood saints and spiritual treasures the Church killed or threw out.” Jervis is a “holy fool,” Duncan said, a literary tradition the author loves.

Duncan was born in Portland and described leaving it seven times in younger years, each departure an attempt to live closer to nature, only to be drawn back to the city for financial survival.

“I had my own ideas about what education was, and it was not institutionalized,” Duncan said of his youth. After his last day of high school, he had one thought about the experience: “I want to erase it from my mind completely. I don’t want to remember anything that was set forth to me as an example of how I should live.”

So, after an all-night party with fellow graduated seniors, Duncan camped alone by a lake in the Cascade mountains, where he consulted three wisdom texts, one of which recommended fasting to let sunlight, air and water “purify” you. He fasted for a week. “I felt like I was just shedding the poisons of a lifetime. I felt very sick and weak. On day five, this other kind of energy started coming. I was just feeling so connected.” When he was 20, Duncan spent more than a month in India, where he fell very ill but also felt spiritually transformed. (A character in “The Brothers K” makes a similarly searching trip there.)

Asian wisdom traditions and an Emersonian reverence for what can be learned from nature have always suffused Duncan’s work, but in “Sun House” they are front and center on nearly every page. “I just can’t not write about mystical experiences, because I have them and they’re as real as what we’re doing right now, just for the duration of whatever it is you want to call what I’m experiencing.” These experiences happen mostly on the edges of sleep, Duncan said. He doesn’t go into more detail about them in conversation but has written about them in personal essays. “Bird-watching as a Blood Sport” begins: “On certain nights when I was a boy, I used to lie in bed in the dark, unable to sleep, because of eyes — staring, glowing eyes, arrayed in a sphere all around me.”

Duncan raised two daughters with his now ex-wife, the sculptor Adrian Arleo, in the time between novels. He also devoted a lot of time and spirit to environmental causes, even if public fights don’t especially suit his temperament. He remembers being at a protest in Portland in 1970 when he realized that the agitators intended to break into a courthouse and get arrested. All he wanted was to leave and “take a long walk along the river,” he said.

But in the years since “The Brothers K” appeared, Duncan battled hard (successfully) against ExxonMobil’s efforts to use Montana as an industrial corridor to the oil sands in Alberta, Canada, and (less successfully) against the building of dams that would have disastrous effects for the region’s wild salmon. Those battles sapped him. When I told him that it sounds like he’s been disillusioned about effecting change, Duncan said: “Yeah, that’s very true. I’m just not interested. Who knows how many years I have left, but not a ton.” He wants to spend those years, he said, writing as well as nurturing a nascent romance.

As we ate dinner on the very sunny rooftop of one of his favorite local restaurants, he said of the state of the world: “I’ve learned not to hope. I’m sorry to say this, but you’re going to make me go dark. I don’t think there’s going to be a remodel. I think it’s going to be a demolition and then a recovery. Try to remodel [Texas Gov.] Greg Abbott and leave something standing.”

Duncan was hesitant to discuss the beguines, an order of feminist, non-cloistered mystics who lived in self-sufficient communities in the 13th and 14th centuries, who serve as an inspiration to the characters in “Sun House.” (“You’ve landed right on a real minefield of spiritual secrecy.”) But from the little he said — and more, from what’s in the book — it’s clear that he thinks they offer a model for how some of our long recovery might occur. “Because they were forbidden to study theology or assume priestly powers,” he writes, “they had nothing to say about the God of threats and punishments and didn’t ‘police’ those they served. They just counseled, regaled, educated, fed, healed and offered safe haven to them, and as a result were loved by the masses almost everywhere beguinages sprang up.”

Duncan’s novels can be raucous at times, and broadly funny. In person, he is easy to laugh and often witty, in a drier way than in his fiction. He is also relatively easy to cry, or at least get choked up, while discussing his feelings for Thomas Mann’s “Buddenbrooks” or the deaths of friends (not a common compliment, but Duncan seems like someone you would want around if you were dying) or even while reading passages from his own work, which he sometimes does as if someone else had written it. There is a subtle rasp to his gentle voice.

In talking about his inner life, he can move between profoundly sincere and winningly self-deprecating. He described once expertly navigating his way through a London neighborhood his first time there, figuring that the explanation for his knowingness “had to be past-life crap.” I repeated that flip phrase back to him with a laugh. “You don’t want to get all precious about it,” he said. “Either somebody will shoot you, or you move to Sedona. New ageism does not do it for me. Right up there with piety; it’s the same thing in a different flavor.”

Likewise, he swings pleasurably between articulation of his beliefs and an appreciation of the vivid, quirky life around him in Missoula. “The bedrock for me is, I really believe in the indestructibility of the soul as a spark that makes us alive,” he started saying over dinner. He interrupted that thought to point out a local man he knew, walking on the street below us, who had named himself Danger. “It had to happen,” Duncan said of the self-christening. “It made sense when he told us.”

After Doubleday issued “The Brothers K,” Duncan owed the publisher a second novel. Instead, he gave them “River Teeth,” a collection of nonfiction, in 1995. He eventually bought his way out of the contract, and in 2006 he signed up with editor Michael Pietsch at Little, Brown for what would become “Sun House.”

Pietsch knows his way around a long, uncontainable novel — David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest,” most famously. In the early 1980s, as a young assistant at Scribner, Pietsch tried to persuade his bosses to publish “The River Why,” to no avail. But Pietsch told me the experience did leave him with “unique, funny, warm, brilliant” letters from Duncan; missives that are still in a folder he has “carried from job to job for 40 years now.” Pietsch called the novelist an “abundant, exuberant correspondent” and said, “I just have a tiny sense of this giant web of correspondence he has with people all over the world.” Duncan’s good literary friends and pen pals have included Wendell Berry, Jim Harrison, Barry Lopez and Brian Doyle, and his epistolary habit migrates into his fiction, where characters often swap soul-baring letters. In “Sun House,” there are also many journals and notebooks through which we learn about the characters who keep them.

Duncan credits Pietsch, now the chief executive of Hachette Book Group — which owns Little, Brown — with helping him strategically cut some of the book’s length and with winning an argument about how the novel should start, which Duncan admits was for the better. Pietsch talks about the experience of working with Duncan as a long-awaited pleasure and seems unfazed by how long it took the author to deliver. “My sense is that he was always working steadily and hard, working at the pace that would allow him to create this,” Pietsch said. “The question of time is just how long it took him to achieve what he set out to achieve.”

In an email interview, novelist Richard Powers, a prominent early admirer of “Sun House,” expressed awe at Duncan’s process: “The time, energy, focus, precision, invention, scholarship, fun, joy, love, courage and compassion that went into making this novel boggle my mind,” he said. “Just contemplating its creation is something of a spiritual journey in itself. Finding this kind of expansive refreshment at this most narrow-minded moment in history is a gift.”

Pietsch, a “long-lapsed Catholic,” said he was nevertheless enthralled by the book’s mystical nature. “He’s writing about people who were born inside an America during a stretch, or a century, that’s in a kind of spiritual void,” Pietsch said. “People come from these suburban no-places. If they want to connect to something bigger and deeper, they really have to strike out on their own.”

On one hand, Duncan has learned to be self-protective about his most earnest side. But he feels strongly compelled to help those connection-seekers whom Pietsch described.

“I want to leave tools that my daughters’ generation and younger can find,” he said. “So many of the young are in despair because they look at our generation, or the one in between them and me, and see a bunch of people who have gone cynical or just are so full of despair, but still flapping their gums. I’ve been fortunate enough to be privy to forms of consolation that the young haven’t even imagined.”

John Williams is the editor of Book World.

Little, Brown. 776 pp. $35

A note to our readers

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program,

an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking

to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.