A hubbub immediately erupted in Silicon Valley, where investors, tech executives and entrepreneurs — still hyping artificial intelligence — were enthralled with the idea that the potential breakthrough could become the first revolutionary leap forward in tech in years. A so-called room-temperature superconductor could make possible sci-fi-like ideas such as levitating trains, as well as more practical ones related to perfectly efficient energy storage.

The topic was so hot that the leaders of influential tech start-up incubator Y Combinator sent out a request to graduates of their program asking whether anyone had experience in materials science, according to a person familiar with the private forum, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share private discussions. The post triggered hundreds of replies debating whether the South Korean discovery was legitimate or not.

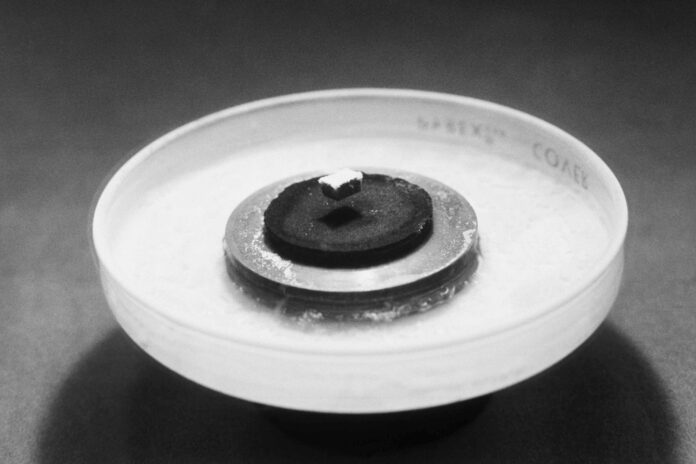

Already, many scientists believe it was a false alarm, and the material, known as LK-99, might just be a type of magnet, though studies are ongoing. But the episode revealed the intense appetite in Silicon Valley for finding the next big thing after years of hand-wringing that the tech world has lost its ability to come up with big, world-changing innovations, instead channeling all its money and energy into building new variations of social media apps and business software.

“The market right now is very much in this shoot first, think later mind-set,” said Bryan Offutt, a venture capitalist at Index Ventures. “If you’re wrong no one will remember, but if you’re right you’re forward thinking.”

Silicon Valley’s boom and bust cycles have been rolling for decades. The dot-com crash of the early 2000s wiped out a swath of companies that had tried to capitalize on hype around the early internet, but also set the stage for the next wave of tech investment. Since then, innovations such as cloud storage and the smartphone have allowed thousands of start-ups to thrive, shifted much of society onto the internet and made Big Tech companies like Google, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft into some of the most powerful organizations in history.

(Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post. Interim CEO Patty Stonesifer sits on Amazon’s board.)

But many tech leaders are nervous that the current focus on consumer and business software has led to stagnation. A decade ago, investors prophesied that self-driving cars would take over the roads by the mid-2020s — but they are still firmly in the testing phase, despite billions of dollars of investment. Cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology have had multiple hype cycles of their own, but have yet to fundamentally change any industry, besides crime and money laundering. Tech meant to help mitigate climate change, like carbon capture and storage, has lagged without major advances in years.

Meanwhile, Big Tech companies used their huge cash hoards to snap up smaller competitors, with antitrust regulators only recently beginning to clamp down on consolidation. Over the last year, as higher interest rates have cut into the amount of venture capital and slowing growth has caused companies to pull back spending, a massive wave of layoffs has swept the industry, and companies like Google that previously said they’d invest some of their profits in big, risky ideas have turned away from such “moonshots.”

Since the launch of ChatGPT last November, AI has captivated the industry, with Big Tech companies and start-ups alike doubling down on the field, heralding it as the next wave of massive growth. But AI is expensive and complicated to develop, and already there are signs that growth is slipping, such as the number of people using ChatGPT every month dropping.

Materials science has helped make tech faster and better for years, from the computer chip to fiber optic cables. Scientists say the field will lead to the next wave of breakthroughs, be it room-temperature superconductors or materials that lead to working quantum computers — which can theoretically operate many times faster than regular computers.

The idea in recent weeks that a mystery material cooked up in an anonymous lab could usher in a world torn from the pages of a sci-fi novel was too irresistible to ignore for many.

“This is the first time in a very long time that I’ve seen so many people share a unified voice about optimism about an abundant future, optimism about a big breakthrough rather than get on social media to share a voice about fear and anger,” tech entrepreneur David Friedberg said on the All-In podcast.

Room-temperature superconductors would be especially relevant to the tech industry right now, which is busy burning billions of dollars on new computer chips and the energy costs to run them to train the AI models behind tools like ChatGPT and Google’s Bard. For years, computer chips have gotten smaller and more efficient, but that progress has run up against the limits of the physical world as transistors get so small some are now just one atom thick.

Sinéad Griffin, a physicist and quantum materials researcher at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, started getting a flurry of emails and texts from colleagues and friends the day the paper first appeared. Claims about room-temperature superconductors are fairly common, but this one intrigued her because it was clear the South Korean researchers had been thinking about their work for a long time, she said.

Griffin and her team soon modeled LK-99 using super computers, showing that it had some features that resembled high-temperature superconductors. She posted the paper online, and suddenly the number of accounts following her on Twitter, which was recently renamed X, skyrocketed.

Here I looked at a few reasonable values of U to ensure that I was getting a good match with whatever exp data we had (structure), and that the physics we were focusing on didn’t vary much with this parameter. pic.twitter.com/DQFjGXjcvx

— Sinéad Griffin (@sineatrix) August 2, 2023

Venture capitalists, tech executives and entrepreneurs sent her emails asking for investment advice and offering paid consulting positions and full-time jobs, she said. Her paper was discussed by hundreds of people on Reddit threads. Much of what people were saying was inaccurate.

“The hype can be damaging,” Griffin said. “That was definitely a huge downside. The upside is people are paying attention to this critical part of science that all of the tech industry depends on.”

Big Tech companies such as Google, Microsoft and Amazon have spent billions over the past decade on AI research, helping create the breakthroughs that led to generative AI tools like chatbots and image generators. But materials science gets less attention, even though it’s a field that underpins much of modern technology.

“Working in this field and in materials research in general, I’m aware of the silent fingerprint that innovations in material have over every aspect of our lives,” said Inna Vishik, an associate professor and quantum materials researcher at the University of California at Davis Department of Physics and Astronomy.

Some of Silicon Valley’s most powerful leaders have a background in materials science. Google CEO Sundar Pichai did his undergrad in metallurgical engineering and has a masters of science from Stanford University’s materials science department. In 1995, Tesla founder Elon Musk was accepted into a doctoral program, also at Stanford, but dropped out two days after it started to pursue his career as an entrepreneur.

“Take Materials Science 101. You won’t regret it,” Musk tweeted last September.

Scientists generally agreed that superconductivity could occur only at extremely low temperatures, making it impractical for real-life applications. But in 1986 German and Swiss physicists found materials that could be superconductive at temperatures high enough to be cooled by liquid nitrogen, a relatively cheap way of lowering an object’s temperature.

The breakthrough led to an explosion of excitement very similar to the one that happened this month. Time Magazine’s cover story May 11, 1987, celebrated the “superconductivity revolution,” complete with a futuristic-looking car plugged into a wall charger. The 1987 gathering of the American Physical Society was so charged with hype and public interest that it’s still remembered as the “Woodstock of physics,” after the famous 1969 music festival.

The researchers behind the discovery won the 1987 Nobel Prize for physics just 19 months after submitting their paper on the topic, the shortest time ever from a discovery to winning the prize.

“If you think there’s a lot of hype right now, it’s nothing compared to back then,” Vishik said.