My curiosity about how the pandemic would shake out was piqued because the books I cover are domestic suspense. The danger in these books can be a person, a family secret or a ghost; but whatever form the evil is taking, it’s coming from inside the house.

In the early days of lockdown, all suspense was domestic. Suspense writing allows for infinite possibilities: There are always new ways to be afraid, new things to be afraid of. The question for the pandemic thriller, or pandemic noir, was how people would continue to do awful things to one another while maintaining social distance. In pandemic noir, the world has gone dark, murky, unpredictable; we are cut off from the people who comprise our support systems and thrust into new situations that are supposed to compensate. They don’t.

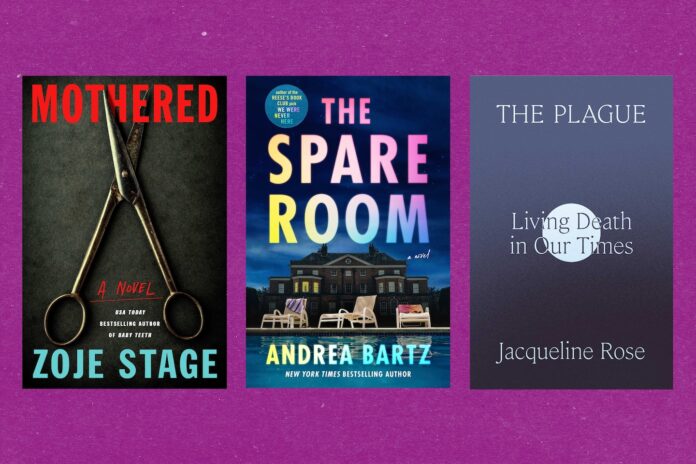

As fiction about the pandemic keeps trickling in, even the lighter books have a sense of gloom and paranoia. The strongest commonality is the exploitation of the most basic familial tie: mother and child. That dyad can and has produced an explosion of genres: horror, domestic suspense, psychological thriller, gothic and noir.

In Zoje Stage’s “Mothered” (Thomas & Mercer, $28.99), the pandemic derails one woman’s plans and replaces them with a visiting mother. Soon after buying her first house in a working-class neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Grace faces the reality of paying a mortgage from no income: She is a hairdresser, and the salon where she works has closed. When Jackie, her estranged mother, gets in touch to say her latest husband has died and she’s at loose ends, Grace invites her to stay and help with expenses. The subtext of “Mothered” is the subtext of the pandemic, with all of its sweeping paranoia and stubborn refusal to stick to a schedule, or a timeline:

How long can this last? Grace thinks.

Indefinitely, Jackie silently replies.

Cue the horror theme: Stage expertly melds her brand of dread with a crime story lying just beneath the surface. Grace’s paradoxical hobby is catfishing young women to build up their self-esteem, but Jackie finding out about it sucks all the pleasure out of helping damsels in distress. Rather than bond with Grace in the present, Jackie adamantly brings up the past: especially Grace’s disabled twin, who died under circumstances mysterious enough to keep Grace feeling guilty and uncertain about whether she might have had a hand in the death. Mothering, in “Mothered,” is not an act not of mercy but a dose of mayhem. Mothers confuse us with their impossible expectations and long, long memories. Mothers confound us with their insistence that their way is the right one — the only right one. But, in happier times, mothers are supposed to console us. Not Grace’s.

In Laura Lippman’s “Prom Mom” (William Morrow, $30), a woman named Amber Glass returns to her hometown of Baltimore to wait out the pandemic. “Prom Mom” was her name in the local tabloids for years, years after that prom was long over and the baby she delivered was a distant memory even to the tabloid readers and the angry people who attacked her once the story hit the news. Amber knows the present contains the past, and that the division between the two is not always neat. Lippman has been writing stealthy, stand-alone novels for a while, after a successful early series featuring the P.I. Tess Monaghan, and in this latest she hits the perfect balance of true-crime sensationalism and sophisticated noir. Women have secrets and men have power — enough power that they could make those secrets, and the women keeping them, disappear.

When Joe, the father of that ill-fated baby (“Prom Dad” doesn’t have the same ring), walks into the art gallery Amber has rented in Baltimore, their old flame is still very warm. Their affair keeps Amber busy and Joe from fretting about lying to his wife about their troubled financial condition. Being together leads them into another perilous adventure. Will eager Amber do what Joe’s always dreamed of, something that might be even worse than their past deeds?

Andrea Bartz’s “The Spare Room” (Ballantine, $28.99) has the elements of a run-of-the-mill domestic thriller but offers the reader something that can be surprisingly hard to find in crime fiction: sex, and not the vanilla flavor. Kelly’s relationship with her fiancé is in trouble due to pandemic circumstances — after much postponing and worrying, her fiancé calls off their wedding for good, which Kelly takes as a sign that it’s time to leave their tiny, miserable apartment in Philadelphia. She impulsively reaches out to an old friend, Sabrina, via social media. Sabrina is a glamorous, married writer who invites Kelly to come stay in the spare room of her large house in remote Virginia. Sabrina and Kelly have not been close in years, but Kelly is scrambling for a place to stay, and she’s always been curious about how Sabrina’s life had turned out. It’s all she dreamed of and dreaded: a handsome, if suspicious, husband, Nathan; a career as a best-selling author; a sprawling house in a woodsy gated community resplendent with pool and other amenities. It’s not long before Kelly is sharing not just the house, but the bedroom, with Sabrina and Nathan. She is surprised to find herself very happy in a world of three. But there was another young woman living in the spare room before Kelly arrived, and that girl has disappeared. Kelly wonders if her hosts had anything to do with the vanishing, and if she’s just avoiding making real choices for the rest of her life by hiding in the spare room. (Yes, that’s all I’ll tell you.) Oh, and there’s also a baby in the background of this story, and it’s not a happy one.

D.W. Winnicott’s idea of the “good enough mother” came to mind after I’d put the novels aside to look at two slim books theorizing issues around the pandemic. Jacqueline Rose is a semi-lapsed Freudian and very sharp literary critic. Her new book, “The Plague: Living Death in Our Times” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $27), starts out in Camus and then wanders to the present day through Freud and other thinkers. Rose is adamant that her book is the link between the pandemic and the war in Ukraine; that personal and civil unrest are our emotional backdrops these days. It’s not uplifting, but it’s interesting and persuasive. I will not forget it soon — like lockdown itself, Rose has made me think in a way that is both more sophisticated and destructive. The quotation from Winnicott that Rose has chosen as an epigraph could become a widespread rallying cry: “May I be alive when I die.” Winnicott wrote it his unfinished autobiography; it’s a common sentiment these days.

From one satisfying dark book by a theorist steeped in pandemic themes, I turned to a profoundly different book: Kate Zambreno’s “The Light Room” (Riverhead, $28). “The Light Room” is addressed to the children — after all, they’re our future. If Rose is concerned with how we will survive this pandemic and what our society might look like after its damage is done, Zambreno’s book has a Vaseline-coating-the-lens quality, wanting to suck some joyful marrow from our enforced isolation. Zambreno proclaims that she favors the miracle of survival over the reality of damage and destruction, and there are many passages that make this familiar comparison. There is transcendence for her everywhere: trees, goats, sleep — all lead into a fantastic world. Her depiction of her children as wide-eyed engines of wonder and truth is tiresome as a trope. There are scattered sections about what Zambreno is reading or thinking about — Derek Jarman, “Walden,” Joseph Cornell, David Wojnarowicz, the Titanic, Elon Musk — that all somehow circle back to her children. Rose has more concern and advice about the future than Zambreno, who seems content to describe the pandemic adventures she invented for her daughters, as if there is a Best Mother of the Pandemic trophy to be won.

No one wins a pandemic. The best you can hope for is a participation trophy and a negative coronavirus test.

A note to our readers

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program,

an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking

to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.