The sarin-filled rockets that fell on suburban Damascus in August 2013 killed over 1,400 people. A mountain of evidence implicating Syria’s government continues to grow.

“What’s happening?” Hijazi called, peering into the dark.

“Come down, I can’t talk,” the voice said.

Hijazi, then a 26-year-old amateur videographer living in the outer suburbs of Damascus, Syria, stumbled outdoors clutching his camcorder. It was not yet 3 a.m., but it was soon clear that a calamity had struck. Strange rockets had fallen in the neighborhood overnight, and an invisible poison was spreading through the warrens of apartment buildings east of the capital. Hundreds of people were dying.

Hijazi hurried to a nearby hospital as throngs of the stricken were beginning to arrive. As he approached the building, he could hear shouts and wails, and see workers moving the bodies of the dead onto the sidewalk to make room. The sight of the freshly arriving victims would scar his memory for the rest of his life.

“I saw the most horrifying scene,” he said. “I saw men, women and children, falling and dying, outside the hospital, in front of the hospital. It was like Judgment Day.”

Hijazi began taking videos, recording everything. At one point, he trained his lens on a small girl. She was about 6 years old, wearing a red shirt and a pendant in the shape of a heart. She lay on the bare floor, quietly gasping for breath.

“She was visibly choking, dying,” he said. “I wondered, ‘Why don’t I throw the camera away and try to do something to help this kid who’s dying?’ Yet there was nothing I could do.”

He steadied himself and kept recording.

The sarin gas attack on civilians in Ghouta, Syria, on Aug. 21, 2013, may well be the most thoroughly documented atrocity of its type in history. Yet, a decade later, it is a crime for which there has been no real punishment — and strikingly little accountability.

Many thousands of photos and videos captured the immediate aftermath, as a small army of volunteer documentarians like Hijazi dutifully recorded the events, along with journalists, medical workers and residents. A U.N.-appointed team traveled to affected neighborhoods within days to interview survivors and to collect biological samples and fragments of the rockets, some of which still contained liquid sarin, the deadly nerve agent unleashed on three opposition-held neighborhoods that night.

A mountain of evidence pointing to the Syrian regime has continued to grow. Intelligence agencies and weapons inspectors collected Syrian documents, witness statements, intercepted communications and other evidence — some of it never published — related to the Syrian military’s preparations for carrying out the attack as well as panicked conversations among Syrian officials after the scale of the casualties became clear.

The gassing of thousands of people with an outlawed nerve agent shocked the world and struck many experts at the time as inexplicably reckless, occurring as it did on the outskirts of a major capital within easy reach of TV camera crews. At the time, just over two years after massive street protests across Syria erupted into civil war, President Bashar al-Assad’s government appeared at risk of collapse, and his army, with crucial backing from Syrian allies Iran and Russia, had turned to ever more brutal tactics in an effort to crush the rebellion, which Assad denounced in speech that year as a “terrorist” movement led by a “bunch of criminals.”

The attack, which U.S. officials say killed more than 1,400 people, was the second-deadliest use of chemical weapons against civilians of all time, exceeded only by Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein’s mass poisoning of ethnic Kurds in northern Iraq in 1988.

Yet, to date, none of the images or forensic data collected in the attack’s aftermath have ever been used in a trial. Neither the United Nations nor the International Criminal Court has ever brought formal proceedings against the Syrian government, which is overwhelmingly implicated in the Ghouta attack, according to multiple independent groups that reviewed the evidence. The world’s chemical weapons watchdog, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), has found Syria’s government culpable for other chemical attacks but has not launched a fact-finding probe to attribute blame for what was by far the most serious.

The reasons are complicated. Experts mainly blame Russia, Syria’s most important ally. Moscow has used its U.N. Security Council veto and influential position on international agencies to block official inquiries into the 2013 attack, in much the same way as it has stymied international investigations into alleged war crimes by Russian soldiers in Ukraine.

But the United States and other Western countries also have come under harsh criticism for a fumbled early response to the attack and for not acting decisively when Syria found a way to continue using chemical weapons by shifting from banned nerve agents such as sarin to ordinary — but still deadly — chlorine gas. Meanwhile, much of the world appears to have simply moved on, with more than 20 Arab countries voting in May to normalize relations with Syria after a years-long boycott.

Survivors of the attack refuse to give up. For many victims and their supporters, Aug. 21 has become a powerful symbol encompassing hundreds of alleged war crimes in a conflict that has killed at least a half-million people. It also has come to represent the Syrian opposition’s best hope for eventually bringing Assad and his top generals to trial for crimes against humanity.

The photos and videos taken by Hijazi and others have become part of a massive archive that continues to grow, as Syrian exiles and human rights groups ferret out new evidence, including forensics studies and government documents smuggled out of the country by defectors. In the past two years, criminal cases stemming from the Ghouta attack have been filed in three European countries, and a network of lawyers and activists is exploring novel legal theories that could allow the first international criminal prosecution of the Assad government to move forward in the coming months.

Supporters of the plan acknowledge it is unlikely that Ghouta survivors will see their former president in the dock in the near future. But even a trial in absentia will send an important message to Syrians and to the rest of the world, said Stephen Rapp, the State Department’s ambassador at large for war-crimes issues at the time of the attack.

“Assad wanted to make Ghouta unlivable for the civilian population, and used sarin gas to murder at least 1,400 innocent men, women and children,” said Rapp, who now advises survivors on their legal strategy. “This was the violation of a rule universally recognized for the last 10 decades — and a crime that can never be justified.”

Death on a historic scale

For Syria, the timing of the attack could hardly have been worse. Months earlier, the president of the United States had sternly warned the Assad government that any use of chemical weapons would transgress an American “red line,” strongly implying that the response would include a U.S. military strike. On the very day of the attack, a team of U.N. fact-finders was in the capital to investigate allegations that outlawed chemical weapons were being used in Syria’s civil war.

Even the U.N. investigators initially were baffled by the decision to launch a massive chemical attack during their visit — and one so close to the capital that they could see the streaks of the outgoing rockets from their hotel windows. Syria and Russia have repeatedly promoted, without evidence, claims that rebels unleashed poison gases on their own neighborhoods in a false-flag operation intended to draw U.S. and European countries into the civil war. The Damascus regime, which would eventually acknowledge that it manufactured sarin in industrial quantities and kept it in ready-to-use stockpiles until 2013, has denied ever using chemical weapons, including on Ghouta.

“We wish here to state categorically that we have never used chlorine or any other toxic chemicals during any incidents or any other operations in the Syrian Arab Republic since the beginning of the crisis and up to this very day,” Faisal Mekdad, a top Syrian diplomat who is now the country’s foreign minister, said in 2015.

Investigations would prove otherwise. Crucial evidence was uncovered in the immediate aftermath of the attacks. More has turned up in the years since.

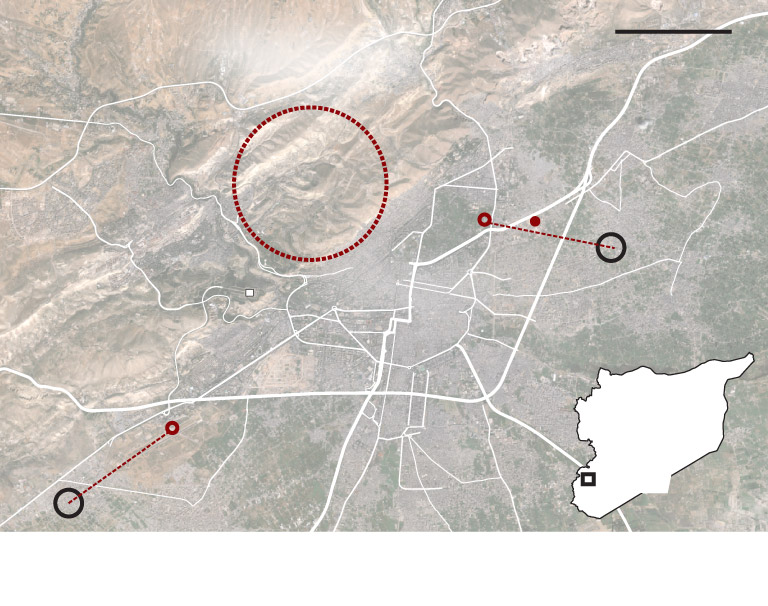

Approximate location

of the Republican Guard

104th Brigade

Sources: Human Rights Watch, potential launch sites

location from Western military officials with access to

intelligence reports on the events.

Approximate location

of the Republican Guard

104th Brigade

Sources: Human Rights Watch, potential launch sites location from Western

military officials with access to intelligence reports on the events.

Approximate location

of the Republican Guard

104th Brigade

Sources: Human Rights Watch, potential launch sites location from Western

military officials with access to intelligence reports on the events.

The first important clues were discovered by the U.N. team that happened to be on the ground at the time. Traveling unarmed and unescorted through no man’s land, braving snipers and ambushes along the way, investigators traveled to the stricken neighborhoods and found remnants of the specialized artillery rockets that had slammed into several opposition-held neighborhoods across an area spanning several miles east and south of Damascus. Some of the rockets, a later forensic examination concluded, used Soviet-designed engines fitted with large cylindrical canisters that release highly volatile liquid poisons on impact. The rockets’ trajectories showed that they had been launched from government-controlled areas to the north and west.

The weapon itself was indisputably sarin, of the high purity that is typical for state-run military programs. One of the deadliest known chemical poisons, sarin is difficult and dangerous to make. Tests showed that the specific sarin used in the attack contained a unique blend of ingredients that matched precisely the formula the Syrian military had used in its weapons since the 1980s.

The effect was devastating. Because sarin is heavier than air, the deadly gas hugged the ground and seeped into basements and bomb shelters where families with children had taken refuge from artillery strikes the night before. Of the deaths, about a third were children, many of whom died in their pajamas.

“It’s pretty sinister,” Ake Sellstrom, the Swedish medial professor who headed the U.N. fact-finding mission, said in interview for a 2021 book on the chemical attack and its aftermath. “First you do a bombardment, which means that you put people in shelters. And when you have people in shelters on a morning like that, you spread the gas, which you know will come down into the shelters.”

In the years since, subsequent investigations have strengthened the evidentiary case pointing to Syria’s regime. Improved testing methods in 2017 enabled a joint U.N.-OPCW team to more precisely link the Assad government’s existing sarin stockpile to the nerve agents used in the attacks against civilians. The samples contained not only the same ingredients but an identical molecular makeup.

OPCW inspectors would find further evidence of Syria’s possession of rockets similar to those used in the Ghouta attack. A team of investigators searching through a government-controlled warehouse near Damascus in 2015 found one such rocket, capable of carrying either conventional explosives or chemical weapons, still in a wooden packing crate bearing stenciled markings showing its delivery to the government-control Syrian port of Latakia.

A photograph of that rocket with its distinctive cylinder-shaped warhead was shown to The Washington Post. The discovery of the rocket was mentioned in a confidential report shared with OPCW member states, including the United States. The finding is seen as a “direct connection between the munitions used in the Ghouta attack and the Syrian chemical weapons program,” said Gregory D. Koblentz, director of the biodefense graduate program at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government.

Some OPCW officials also deduced from records that there may had been inadvertent casualties from the chemical attack inside Syria’s military, according to Western officials who reviewed the evidence. Syrian government officials privately told the inspectors that several people attached to Syria’s elite chemical weapons unit died just days before the Aug. 21 attack, in an incident that the Assad government has never acknowledged or explained. The timing of the mysterious deaths suggests a possible accident during operations to fill the rockets with sarin, the official said.

The accident, if it happened, could also reflect the Assad government’s limited experience with chemical weapons, which were originally manufactured for use in missiles in a possible future war against Israel. The sarin — classified as a weapon of mass destruction, or WMD — was repurposed for use against Syrian rebels in 2013. Still, before Aug. 21 of that year, such weapons had been used only a handful of times in relatively small amounts, with few casualties. U.S. intelligence officials say they believe Assad authorized the use of chemical weapons and left it to his generals to make decisions about using them tactically to drive rebels and their supporters from their strongholds. A declassified U.S. assessment in 2013 asserted that Assad’s forces began mixing chemicals in preparation for the attack around Aug. 18.

“We think that there was improvisation and limited testing, and then someone at the field level made a miscalculation,” said one Western security official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive intelligence. “The Syrians didn’t know what they were doing, and they underestimated the effect.”

One small comfort, he said, is that the impact could have been far worse.

“In a more crowded area,” he said, “that much sarin, in that concentration, might have killed 10 times as many people.

The OPCW’s investigation of Syria’s chemical weapons program is now in its 10th year, though progress has largely stalled since 2019, when the Assad government effectively cut off access to key sites and documents. Ironically, the watchdog group’s probe into the massive sarin attack in 2013 never even got off the ground — which is why videos and other evidence collected by survivors remain crucial to any effort to hold Syrian officials legally accountable.

Inspectors have publicly named culprits in three other chemical weapons investigations — but not for Ghouta. Their hands were effectively tied by complex legal agreements hammered out by diplomats in September 2013, in the frenzied weeks after scenes from the massacre first flashed on TV news channels around the world.

The Obama administration refrained from launching a U.S. military strike over Syria’s “red line” breach, pausing a plan to attack Damascus initially because of the presence of the U.N. inspection team on the ground. It then collapsed entirely after lawmakers from both political parties overwhelmingly rejected legislation authorizing a strike. President Barack Obama instead accepted a Russian deal in which the United States would defer military action if Syria agreed to join the Chemical Weapons Convention and unilaterally destroy its entire stockpile, under international supervision.

Against all odds, the disarmament plan mostly worked. Over a span of nine months, teams of international experts supervised the removal or destruction of nearly all of Syria’s chemical weapons. (U.S. intelligence officials later concluded that a small portion of the original stockpile was hidden away, and some of it was used in a sarin attack years later in April 2017.) The experts also oversaw the physical destruction of labs and production equipment for making more sarin. Then, in an astonishing technical achievement, the Pentagon converted an old cargo ship into the world’s first floating chemical weapons destruction plant and neutralized nearly 1,400 tons of liquid poisons at sea. As a feat of arms control, it was historic: the first unilateral elimination of an entire WMD program in the middle of a war.

The price was essentially a pass for Damascus on the Ghouta attack. Syria lost its most strategically important weapons stockpile, but under the Russian agreement, Assad was never forced to acknowledge his role in the massacre. His government could be held responsible for future chemical attacks but not past ones.

That hasn’t stopped Damascus from using chemical weapons short of sarin in attacks against rebels and civilians. Human rights groups say there have been more 300 chemical weapons attacks since 2013, the vast majority of them involving chlorine, a common chemical used in water purification and one that Syria possesses legally. While chlorine is far less deadly, using it as a weapon is banned by international law. Yet Syria has done so scores of times, with relatively little international outcry, current and former U.S. officials say.

“The lesson for Assad is he can do anything necessary to stay in power and there will be no accountability,” said Robert S. Ford, who served as the U.S. ambassador to Syria in the early years of the civil war and repeatedly sought to confront Assad over an array of alleged war crimes, from systematic torture and rape to barrel-bomb attacks that deliberately targeted hospitals in rebel-held areas.

“Of the kinds of vicious things the Assad government is doing to maintain itself in power,” Ford said, “gas attacks are at the top of the list. But it’s a long list.”

New cases, novel theories

Taher Hijazi’s list includes crimes that devastated his own family. His brother was a newlywed with a young baby when he was picked up seemingly at random by Syria’s secret police in 2014. Soon afterward, the family learned that he had died in prison. Four years later, Hijazi’s father, a government employee who stayed away from protests and studiously kept his political opinions to himself, was killed in a Russian airstrike on his hometown of Douma, Syria. The family was never allowed to recover his remains.

Hijazi fled Syria and applied successfully for asylum in France. Still, when he thinks of all the horrors he witnessed during the war, his mind inevitably returns to Ghouta and August 2013. He shared his videos and stories with human rights groups, and he was named as one of about a dozen plaintiffs in a French criminal complaint in 2021 accusing the Syrian government of crimes against humanity.

Similar criminal complaints have been filed in Germany and Sweden, each claiming that individual countries have a universal right to bring criminal charges for human rights offenses that occurred outside their borders. Meanwhile, lawyers representing Syrian survivors and advocacy groups are exploring new legal avenues that they hope will lead to an international prosecution, backed by a coalition of countries in multiple jurisdictions. The International Criminal Court, the usual venue for such cases, is not an option, in part because Syria is not a member of the ICC, and the court does not try cases in absentia.

A wide array of governments appear to back the idea of a multicountry prosecution centered on the chemical attack — the clearest and perhaps gravest violation of international law in Syria’s 12-year-old war, according to attorneys representing Syrian survivors. A point of consensus among the participants is that the case “needs to be Syrian-led,” said Ibrahim Olabi, a British attorney specializing in international law.

The Biden administration did not comment on specific legal approaches but said the White House intends to move forward with efforts “promoting accountability for those responsible for these heinous crimes,” National Security Council spokesperson Adrienne Watson said. “We cannot let the world become desensitized to the use or proliferation of chemical weapons,” she said.

Among the available evidence for such a case are the videos taken by Hijazi. And 10 years later, he still becomes visibly emotional when he talks about certain victims his camera lens briefly isolated during the chaos of that evening. Now a father, he thinks often about the little girl in the red shirt, struggling for what surely were her final breaths. He remembers a grief-stricken mother he observed hours later, looking with dread for a familiar face amid the rows of shrouded bodies in a makeshift morgue.

“She was looking for her own children,” he said. “The faces and bodies were covered. She actually had to go through them and remove the cover from each face.” He choked up as recalled the moment. “They were just children,” he said.

Hijazi today doubts he will live to see any of the responsible Syrian officials imprisoned for the crimes he witnessed. But it’s sufficient for now, he said, to know that his videos may have an impact, ensuring at least that the world knows what the perpetrators did.

“There are certain things that give us hope, but not many,” he said of the legal process he has witnessed so far. “Recent experience proves to us that the road to justice is a very long one.”