In August 2021, Sayyid, whose name has been changed for his protection, watched in terror as the Taliban assumed power in Afghanistan. The former field support representative for a U.S. company told Fox News Digital he felt “like a prisoner … sentenced to hanging.”

For four years, Sayyid said, he supported “fielding, installation, operation training and maintenance of the entire Afghan military and police [radio] network systems.” Supporting the Afghan military meant that employees of the company he worked for “performed [their] duties in danger.”

On one occasion, the Taliban fired a rocket at Sayyid’s car while he traveled in a military convoy. Miraculously, everyone inside was uninjured. The event shook Sayyid, who “was always waiting for something bad to happen.”

Sayyid’s work made him eligible for the Afghan special immigrant visa (SIV) program, which grants legal permanent residence in the U.S. for those with qualifying employment on behalf of the U.S. government.

AFGHAN TRANSLATORS LAND IN US, SAY US LEAVING OTHERS BEHIND WHO FACE DEATH THREATS FROM TALIBAN

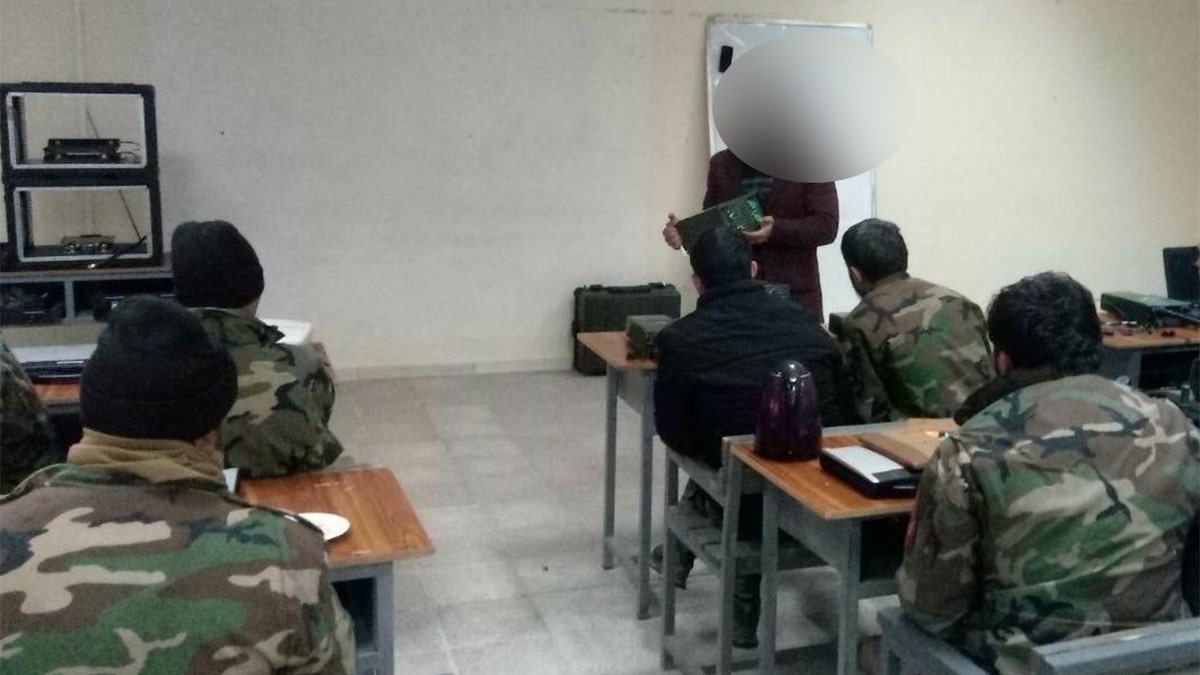

As an employee of a U.S. company for four years, Sayyid spent his weekdays in the field alongside Afghan military and police personnel, sometimes providing training classes. (Photo provided by Sayyid)

In April 2021, Sayyid created a 250-person union to help his fellow employees apply for SIVs. He declined to file his own application until August, when his hopes that the Afghan government could repel the Taliban were dashed.

Two years later, Sayyid is among more than 152,000 SIV applicants who remain in Afghanistan awaiting processing.

The State Department estimates that, as of April 2023, more than 840,000 principal and derivative SIV applicants remain in Afghanistan, according to a new report from the State Department’s Office of the Inspector General.

The SIV program has been dogged by criticism for years because of its shortcomings. Chief among these is the difficulty of obtaining the human resources documentation and supervisory letter of recommendation necessary to achieve Chief of Mission (COM) approval, the first step of the SIV process.

Adam Bates, supervisory policy counsel for the International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP), told Fox News Digital the SIV program “puts immense burdens on the applicants themselves … who, by definition, are people who are in danger.”

Evacuees wait to board a Boeing C-17 Globemaster III during an evacuation at Hamid Karzai International Airport, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Aug. 23. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Isaiah Campbell)

Project Rabbit has been described as a secretive Department of Defense and State Department initiative started after the U.S. withdrawal in an attempt to reduce the burden of proving eligibility for employees of participating contracting companies. By May 2023, IRAP claimed that Project Rabbit was mired in a backlog of cases that could take six years to process.

“Since August 2021, DAS-T has verified 9,906 applicants,” a Department of Defense spokesperson told Fox News Digital. “The number of applicants DoD is able to verify depends on the willingness of companies to provide information on their former employees and the fidelity of that data, but generally the DoD team is currently able to process 200 candidates a week on average.

“Of note, DoD’s efforts supplement the Department of State’s efforts to verify employment and supervisor recommendations as part of the official SIV application process. Combined, these two processes result in a total verification throughput of roughly 2,500 to 3,500 applicants per month. This is the second and only step of a 14-step SIV application process in which DoD has a role.”

The DoD spokesperson took issue with criticism aimed at Project Rabbit.

“Correction: Project Rabbit refers to DoD’s initial, ad hoc effort begun in August 2021 to assist the Department of State with verifying the employment of certain Afghan Special Immigrant Visa (ASIV) applicants who claim they worked for a DoD contractor or subcontractor. In June 2022, DoD changed the naming convention to the DoD ASIV Support Team (or DAS-T) as we transitioned from surge to sustained support.

In this handout provided by U.S. Central Command Public Affairs, U.S. Air Force loadmasters and pilots assigned to the 816th Expeditionary Airlift Squadron load passengers aboard a U.S. Air Force C-17 Globemaster III in support of the Afghanistan evacuation at Hamid Karzai International Airport Aug. 24, 2021, in Kabul, Afghanistan. (Master Sgt. Donald R. Allen/U.S. Air Forces Europe-Africa via Getty Images)

“The Department of State and DoD have multiple processes in place to verify statutory employment and supervisory requirement are met. DoD’s primary role is to engage companies that employed certain applicants and obtain employment information when applicants are unable to contact their former employer or supervisor, which is a smaller subset of the total SIV applicant pool.

“The Department of Defense does not maintain individual employment records of DoD contractor companies or their subcontracted companies and is, therefore, heavily reliant upon voluntary employer participation.”

A State Department spokesperson told Fox News Digital 50% of SIV applicants generally achieve COM approval but didn’t answer questions about how many applicants matched with employer data through Project Rabbit achieved COM approval.

ARMY VET SEEKS TO SAVE AFGHAN COMMANDO STUCK IN TURKEY, LIVING IN FEAR OF TALIBAN

Sayyid received his COM approval in June 2022, ten months after submitting his application. While State Department data show COM processing has sped up in recent months, No One Left Behind’s Director of Advocacy Andrew Sullivan told Fox News Digital that, even at the improved rate, it will take the State Department 5½ years to work through its backlog.

The State Department is bound by a legal mandate, reinforced by an IRAP class-action complaint from 2018, to process SIV applications in nine months. The State Department currently seeks to comply with this mandate by demonstrating that all government-controlled aspects of the SIV process are fulfilled within 270 days, on average.

Taliban fighters celebrate the first anniversary of the withdrawal of U.S.-led troops from Afghanistan at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan, Aug. 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Sullivan pointed to numerous delays outside the applicant’s control that impact the government’s timeline, like getting documentation of service “oftentimes from organizations that no longer exist or [letters of recommendation] from folks they served alongside.” Simply acquiring passports, he said, can take six to 12 months in the Taliban’s Afghanistan.

For Sayyid, surviving under the Taliban has been difficult. In late 2021, an unknown friend or colleague informed on him, leading local Taliban forces to believe that Sayyid could make defunct radio systems operational. The Taliban sought him out with promises of job security. Sayyid evaded their searches by routinely moving between his friends’ homes, burning documents that linked him to the former government and transferring vital records to a family member for safekeeping.

Like many SIV applicants, Sayyid struggled to find work. He sold his family’s possessions to afford food, rent and $2,000 for the passports his wife and children required for evacuation. This year, he found a job with a non-governmental organization to cover some expenses.

In February, Sayyid’s close friend, an author and activist, was murdered by the Taliban. In the same week, the State Department’s Coordinator for Afghan Relocation Efforts (CARE) team informed Sayyid he was eligible for a flight to safety. First, he needed to submit his children’s passports, which took another six months to arrive. Two weeks ago, Sayyid forwarded the passports to CARE. Now, he faces a new roadblock after formal transportation operations were reduced in mid-June.

Taliban fighters hold their weapons as they celebrate one year since they seized the Afghan capital, Kabul, in front of the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan, Aug. 15. (AP/Ebrahim Noroozi)

OUT OF AFRICA: VET GROUPS COME TO RESCUE OF AFGHANS ON TALIBAN KILL LIST

Shawn VanDiver, founder of the #AfghanEvac coalition, told Fox News Digital “there’s a lot of optimism” relocation will soon scale up and surpass prior levels. He expressed pride in coalition volunteers who helped 24,000 Afghans escape Afghanistan since September 2021.

“It’s the most American thing I’ve ever seen,” VanDiver said of the men and women who work without pay “to make a difference in the lives of folks halfway around the world.”

Despite transportation difficulties, No One Left Behind has moved more than 400 principal SIV applicants and around 900 of their family members out of Afghanistan in the past fiscal year, with donated funds and the support of the CARE team and nonprofit partners. Urgency compels their actions. Sullivan said No One Left Behind has tracked reports “littered with heartbreaking details” alleging the murders of more than 200 SIV applicants and allies since August 2021.

A U.S. Air Force aircraft takes off from the airport in Kabul Aug. 30, 2021. (Aamir Qureshi/AFP via Getty Images)

In one report, a former U.S. embassy employee wrote that he watched his friend, a former U.S. Special Forces interpreter, get “shot in front of his two kids” by the Taliban.

Bates finds fault in the State Department’s failures to abide by its legal mandate.

“When people under Taliban threat are waiting two, three, five, 10 years to get their visas, it’s not just some deviation from department guidelines. It’s a violation of the law, and it costs people their lives,” Bates said.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The stress of Sayyid’s two-year wait has left a toll on him and has him questioning his future.”

“I really don’t know if the life I’m waiting for is worth my efforts,” he said.