By Esme Stallard, Jonah Fisher and Sophie Woodcock, BBC News Climate and Science • Becky Dale and Libby Rogers, BBC News data journalism team

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEvery major English water company has reported data suggesting they’ve discharged raw sewage when the weather is dry – a practice which is potentially illegal.

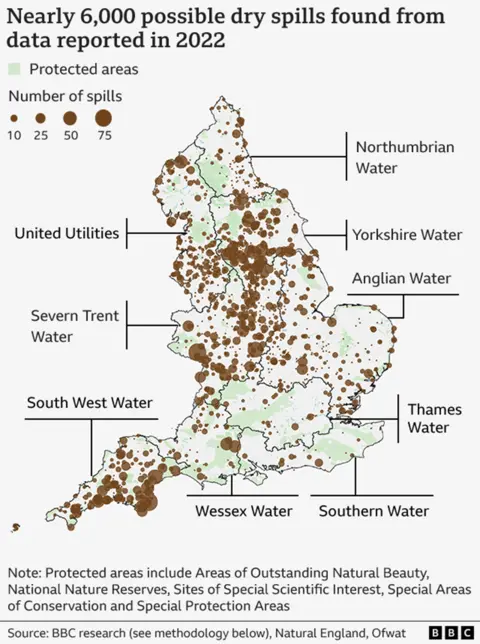

BBC News has analysed spills data from nine firms, which suggests sewage may have been discharged nearly 6,000 times when it had not been raining in 2022 – including during the country’s record heatwave.

Water companies can release untreated sewage into rivers and seas when it rains to prevent it flooding homes, but such spills are illegal when it’s dry.

The firms say they understand public concerns around dry spilling, but they disagree with the BBC’s findings.

They have said the spill data shared with the Environment Agency was “preliminary” and “unverified”, and also disagree with how the BBC defined a dry spill, which they say differs from the Environment Agency’s approach.

The latest findings follow a BBC investigation conducted last year which found 388 instances of possible dry spilling in 2022 by three water companies – Thames, Wessex and Southern – after they shared their data with the BBC.

The other six – Anglian Water, Northumbrian Water, Severn Trent, South West Water, United Utilities and Yorkshire Water – had refused to share data about when they might be spilling with the BBC. They said it could prejudice an ongoing criminal investigation by the Environment Agency (EA) and Ofwat into their activities.

The regulator – the Environment Agency – which had the data, disagreed, and in January handed it to the BBC.

Overflow points where sewage is discharged have monitors which record when spills start and stop.

The BBC cross-referenced the companies’ spill data from these overflow points with local Met Office rainfall data. Over 18 months we analysed data from nearly 10,000 monitors which had recorded more than 1.5 million hours of discharges.

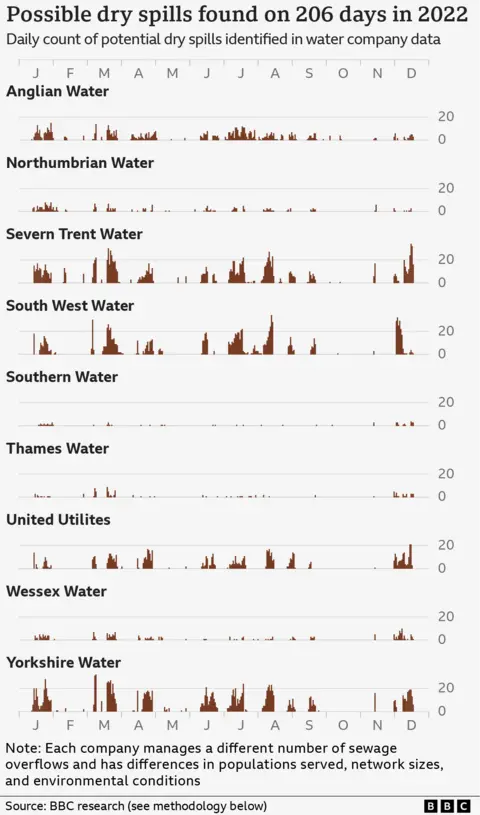

BBC analysis suggests dry spills may have started on more than 200 days in 2022, lasting more than 29,000 hours – including during the record summer heatwave when people were cooling off in England’s rivers and seas.

“We are most concerned about those [spill] events happening in places where people are likely to go in the river,” said Professor Barbara Evans, chair in public health engineering at the University of Leeds.

Consumption of water contaminated with human or animal faeces exposes people to parasites and bacteria such as cryptosporidium and E.coli, which cause diarrhoea and vomiting, or viruses like hepatitis A which can lead to liver infection.

The six water companies who were subject of the latest investigation took issue with the BBC’s analysis, citing the data we used and the methodology.

Every year England’s water companies are required to submit an annual report to the EA summarising their discharges. This enables the EA to investigate potential cases of dry spills and to decide whether it will take any action.

The BBC has been analysing data behind the 2022 report, but in responding to our findings, the water companies argue that the datasets are unverified and contain errors.

Examples of potential dry spills in the data were presented to each water company. Anglian Water disagreed with all the examples presented and the remaining five companies disagreed with some.

The main reason the companies gave for disputing the examples was that their monitors malfunctioned and incorrectly recorded spills.

From 2025, all water companies have committed to publishing near real-time sewage maps for the public to increase transparency. They will use the data from these monitors to create the maps.

David Henderson, CEO of the industry body, Water UK, told the BBC: “We are the most transparent industry in the world when it comes to water. No other country in the world publishes this sort of data.”

In May, Anglian Water was found guilty of failing to provide data to the Environment Agency for their investigation – and it will be sentenced in July.

Regarding the BBC’s methodology, some of the water companies argue it did not take into account that some outlets have large catchment areas and it can take a few days for any rainfall to drain through their systems, i.e. sewage detected on a dry day may be the remnants from an earlier rainy day.

However, the BBC accounted for drain-down time by only considering a discharge a potential dry spill when there had been four consecutive days in the surrounding area without rain.

Helen Wakeham from the EA says the BBC’s methodology is, in fact, “more generous” to the companies than the EA’s.

Commenting on the results of the BBC’s investigation in general she said: “I’m not surprised, these networks haven’t been invested in for decades. That investment needs to take place.”

In May the UK’s top engineers and medical professionals warned in a public report the risk from human faecal matter in our rivers will increase without changes to the network and how we build our cities.

Dr David Butler, professor of water engineering at the University of Exeter, and co-author of the report, said investment from water companies has “not really been up to scratch”.

But he added that we must also rethink how we design our towns and cities.

“What we would like to see is reversing urban creep – that is well beyond the powers of a water company. You see it all the time, people concreting over their front garden,” Prof Butler explained.

“If you could unpick that it would help because that would reduce stormwater runoff and that would give us more capacity in our pipes.”

Reducing dry spilling would also help prevent excessive nutrients entering rivers from sewage discharging. The issue, which is also associated with agriculture, can cause excessive amounts of algae to grow, resulting in waterways becoming depleted of oxygen, killing off other animals like fish.

“[It] also can have knock-on health effects, because this algae can produce other toxic products which might be harmful to human health,” said Prof Evans of University of Leeds.

South West Water said: “We are clear that storm overflows must only be used when absolutely necessary to protect people’s homes and regard all unpermitted dry spills as unacceptable.”

Yorkshire Water and Northumbrian Water said they: “Do not believe the [BBC’s findings] are true reflection of dry discharge numbers.”

United Utilities said: “The information you have received from the Environment Agency reflects unvalidated, raw signals and not validated start/stop times.”

Anglian declined to provide a formal comment on the BBC analysis, but in correspondence to the BBC said that the monitor data was not enough to determine dry spills due to monitor malfunctions, and said the methodology was flawed.

The three companies investigated by the BBC last year also responded to our new findings.

A Thames Water spokesperson said: “There are a number of methodologies for defining and calculating why and how dry day spills occur.

“We regard all discharges of untreated sewage as unacceptable, and we have planned investment in our sewage treatment works to reduce the need for untreated discharges.”

A Wessex Water spokesperson said: “Naturally occurring groundwater can enter sewers, often from private pipes and in dry weather, which can cause overflows to operate for days or even months.

“We agree overflows are outdated so we’re investing £3 million a month to help reduce how often they automatically operate.”

A spokesperson for Southern Water said: “In areas with high levels of residual groundwater, spills can happen outside of periods of rainfall. Without these releases – made up almost entirely of groundwater – homes and communities would be flooded.

“Combatting these groundwater spills is a key part of our £1.5 billion Clean Rivers and Seas Plan, which is designed to drastically reduce all storm overflows across our region by 2030.”

Counting possible dry spills – methodology

Water and sewerage companies are responsible for outlets known as combined sewer overflows (CSOs), which release sewage from treatment works or the sewage network into the UK’s waterways.

The majority of CSOs record when they discharge.

For this analysis, the BBC took the start-stop times of individual discharges from the CSOs and converted them into the standard 12/24-hour counting blocks used by the EA to determine “spills”.

In the specific case of United Utilities, the BBC found that some of the discharge data provided to the EA did not correspond to their 2022 annual report summarising this data. For that reason, the BBC discounted data from more than one-third of United’s overflows.

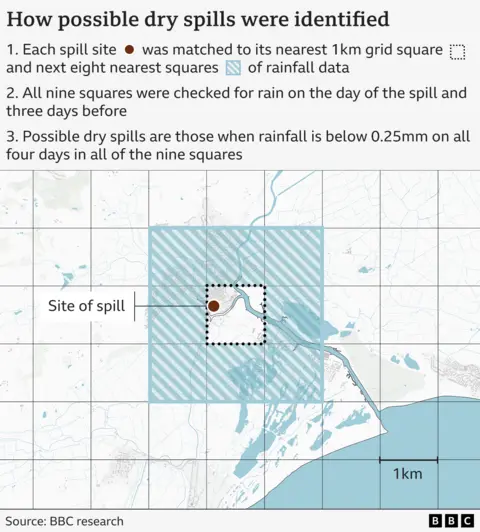

The start times of the companies’ spills were matched to daily rainfall data from the Met Office, which is produced from a network of automatic rainfall gauges and observation stations.

This rainfall data is presented in gridded squares that cover the land area of the UK. Each grid cell is 1km sq.

Each overflow point is part of a larger network, or catchment area, and rain further away can take time to reach the overflow point.

The BBC considered the nine grid squares nearest to each spill site in the analysis. Individual catchment areas may be larger or smaller.

The EA defines a dry day as one during which there was less than 0.25mm of rain and less than 0.25mm of rain the previous day.

But the BBC took a conservative approach of four consecutive days without rain in all nine grid squares to allow for drain-down time.

The methodology was independently reviewed by three academic experts working in this field.

Graphics by Muskeen Liddar. Edited by Greg Brosnan.

Methodology support from Dr Gemma Coxon, University of Bristol; Dr Nick Voulvoulis, Imperial College London; Dr Barnaby Dobson, Imperial College London