He was dismissive of his opponent, Kemal Kilicdaroglu. “Bye, bye to Mr. Kemal,” he said. He denigrated LGBTQ people as a threat to “family.” And he ruled out any release for an imprisoned Kurdish political leader, calling him a “terrorist.”

Similar remarks had been part of his campaign stump speech over the past few weeks as Erdogan tried to distract from Turkey’s economic crisis, marked by soaring inflation. His focus — on threats to the nation and to the fabric of conservative life — helped rally a coalition of supporters that included pious Muslims and hard-right nationalists and gave Erdogan 52 percent of the vote in the runoff held Sunday.

As the country moved on from the election, Erdogan would not easily abandon the bitter rhetoric, analysts said, setting Turkey on a divisive and turbulent course for the foreseeable future, even as Erdogan juggled a need to stabilize the economy as well as Turkey’s often stormy relations with allies in the West.

In fact, “I think he is going to harden” his rhetoric, said Berk Esen, a professor of political science at Istanbul’s Sabanci University. “We are going to see him adopt a very polarizing discourse using ethno-religious themes” to maintain his “winning coalition” of voters.

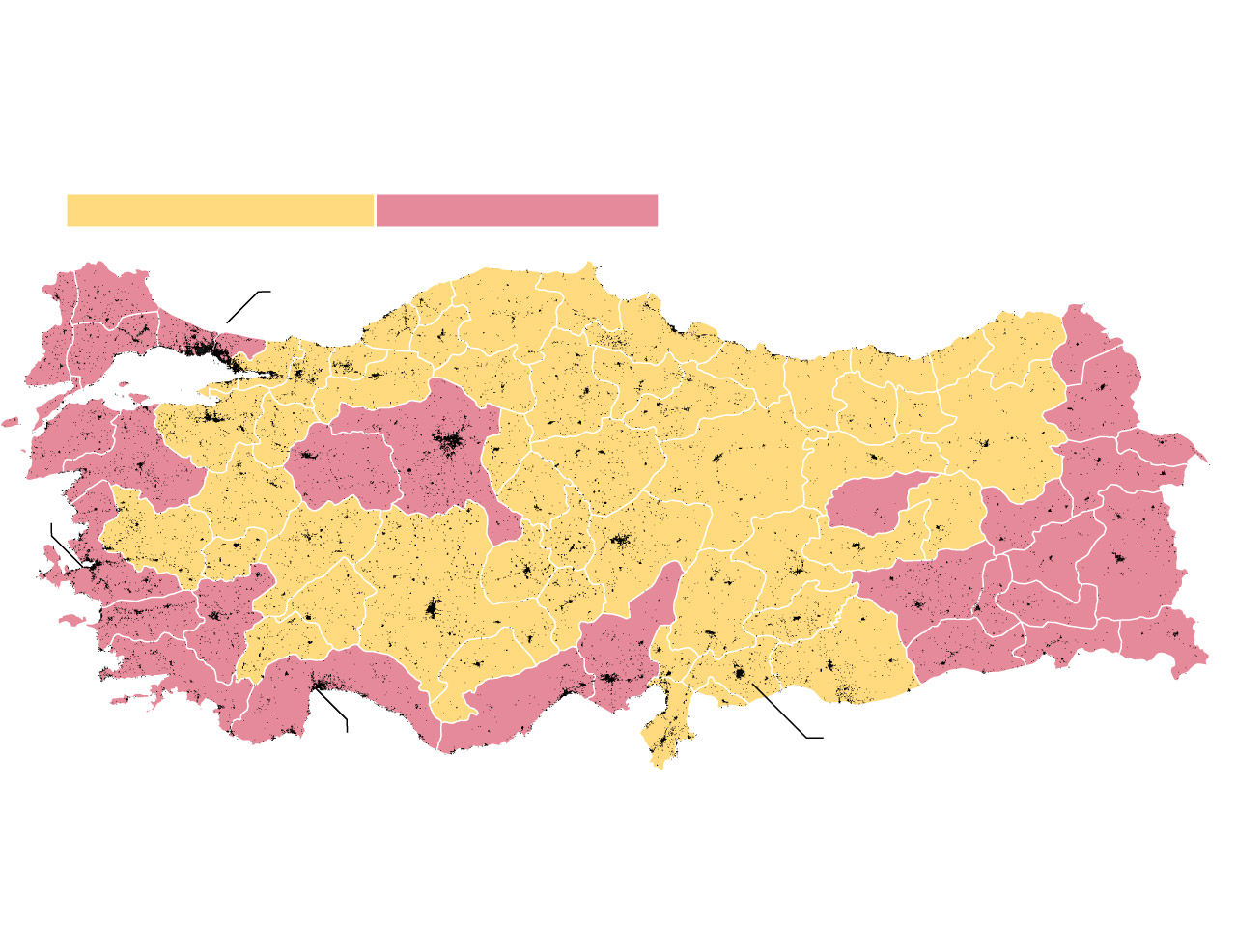

Turkish presidential runoff election

Note: 99.43% ballot boxes opened. Unofficial election results.

Source: Anadolu Agency, worldpop.org

Turkish presidential runoff election

Note: 99.43% ballot boxes opened. Unofficial election results.

Source: Anadolu Agency, worldpop.org

Erdogan’s victory was a blow to opposition supporters who had rallied around Kilicdaroglu’s early campaign pledges, which included a restoration of the country’s democracy, protection for civil liberties and even the release of some of the nation’s most high-profile political prisoners, among them Selahattin Demirtas, the imprisoned Kurdish leader.

As Erdogan railed against LGBTQ people during the campaign, Kilicdaroglu suggested he would allow pride parades, banned under the current government. For a time, Kilicdaroglu promised a more civil public discourse and, most important, change, after two decades with Erdogan as Turkey’s leader.

The government’s mismanagement of the economy and its faltering response to deadly earthquakes in February promised to broaden the opposition’s appeal. But Erdogan, a gifted orator, raised the specter of dark threats to the nation emanating from the opposition, casting himself as the bulwark against chaos.

Last week in central Turkey, for example, Bunyamin Eken, 39, who supported Erdogan, criticized Kilicdaroglu for saying he would release Demirtas as well as a once-obscure civil-society activist named Osman Kavala, held on charges that human rights groups say are baseless. Eken elevated such worries above his own economic concerns, after Erdogan cast Kavala as the leader of a global plot against Turkey.

Kilicdaroglu, who trailed Erdogan in the election’s first round, was forced to adopt more aggressively nationalist themes before Sunday’s vote, including anti-immigrant rhetoric targeting millions of refugees from Syria and elsewhere who have settled in Turkey.

Despite the president’s winning strategy, “I don’t think things are going to be easy for Erdogan,” Esen said. “He doesn’t have the means to rebuild the earthquake zone. He doesn’t have the means to solve the migration crisis. At some point the Turkish economy is going to crash.”

And although Erdogan’s alliance had won a majority of seats in parliament, his own party was dependent on more extreme coalition partners — who oppose women’s rights or greater recognition of Turkey’s Kurdish minority and could demand policies that reflect their concerns, Esen said.

“Erdogan put together a winning coalition based on fault lines: Turkish versus Kurdish nationalism, secular-urban versus the Sunni majority. This is a winning formula,” he said.

“This is not a better formula for Turkey,” he added.

Erdogan will remain in “campaign mode” at least until next March, when local elections are set to be held, said Ozgur Unluhisarcikli, the Ankara director of the German Marshall Fund. At the same time, he “will need to juggle an economic crisis of his own making, and actually, he is running out of ammunition,” he said, noting that Turkey’s foreign reserves had recently fallen below zero for the first time since 2002.

Erdogan’s need to stabilize the economy is likely to result in a foreign policy less turbulent than in the recent past, as Turkey relied on short-term cash flows from countries such as Russia, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. “He will be very careful not to irritate them,” Unluhisarcikli said. Turkey also needs to “appease international financial markets,” which would require that Erdogan stabilize relations with Europe and the United States.

President Biden’s early, congratulatory tweet after Erdogan’s victory Sunday — and a phone call between the two leaders Monday — might show that both countries are interested in de-escalating years of tense relations over Syria and Turkey’s close relations with Russia, Unluhisarcikli said.

At home, though, “the level of tension we witnessed during the last couple of months is not sustainable,” he said. “I don’t expect tension to continue at this level, but I don’t expect consensual politics either. I expect President Erdogan to decrease tensions a little bit, only to re-increase them” before the next election.

For young voters like Ilgin Yilmaz, who voted Sunday for Kilicdaroglu, clinging to the possibility of Erdogan’s defeat even as it looked unlikely, another season of divisive politics seemed too much to bear.

“I was born in the 2000s and I woke up with this government, and now I’m 23 years old and still they are here,” she said. As a woman, she feared the influence of political parties aligned with Erdogan that favor strictly curbing women’s rights. As a medical student, she was angered by the president’s dismissive remarks toward doctors who wanted to leave Turkey over poor working conditions.

“We really hate this government,” she said.