The first cracks started forming in November 2022 across the pond, when Arts Council England (ACE) announced cuts that would leave the London-based English National Opera (ENO) short $14 million from the suspension of an annual grant — i.e. a third of the company’s budget — unless the company relocated to Manchester.

January 2023 saw a slight turn of fortunes for ENO, as the council granted the company an extra year in London supported by a little more than $14 million in holdover funding.

“The ENO and our audiences remain in the dark as to why ACE decided to remove our status as a National Portfolio Organisation, despite us meeting or exceeding all the criteria they set,” ENO said last year in a January statement. “One in seven of our audience are under 35, one in five of our principal performers are ethnically diverse and over 50% of our audience are brand new to opera.”

A subsequent subsidy of $30 million and an extension on the relocation timeline to 2029 have allowed the company to limp toward its Mancunian hometown but have thrown its identity into chaos. Proposed cuts of 19 orchestral players and transference of all musicians to part-time contracts enraged members of the opera community and rattled music director Martyn Brabbins into an October resignation, writing that “the proposed changes would drive a coach and horses through the artistic integrity” of the company.

“This is a plan of managed decline,” he said, “rather than an attempt to rebuild the company and maintain the world-class artistic output, for which ENO is rightly famed.”

It all seemed so far away — a tragedy unfolding on a faraway stage. But the first act is always merely a setup.

Rumblings of trouble stateside grew in June, when Tulsa Opera announced the cancellation of two of its forthcoming productions, reporting a 39 percent drop in revenue in 2022 and projecting a 44 percent drop in 2023.

Then in July, the renowned Chautauqua Institution and its Chautauqua Opera Company and Conservatory announced sweeping operational changes to survive its own financial crisis, slating no new productions for its Norton Hall home.

“This is a period of deep reflection about the future of opera in America,” the organization’s statement read.

In August, the head of Opera Philadelphia stepped down as the company, facing $2 million in budget cuts and a 16 percent reduction in staff, announced the postponement of Joseph Bologne’s “The Anonymous Lover” to the 2024-2025 season.

August also brought news that the Metropolitan Opera Guild would scale back operations — the nonprofit has acted as an assisting organization to the Met since 1935, when its contributions helped the company survive the Great Depression — and with it the publication of the 87-year-old Opera News. (Its final issue was printed in November, and the publication has since been incorporated into the British magazine Opera.)

Met general manager Peter Gelb told the AP the loss was “the result of several years of declining economic fortunes.”

In October, Maryland Lyric Opera called it quits with little explanation in a farewell note posted by founder and artistic director Brad Clark. In November, Syracuse Opera canceled the rest of its season and furloughed its staff of one full-time and four part-time employees.

“While our recent productions have been artistically excellent and impactful, like many opera companies across the country, ticket sales have been considerably lower than projected,” Syracuse Opera board chair Camille Tisdel wrote in a note to members. “… Additionally, given the economic climate and uncertainty in our world, grant support, sponsorship, and donations are all in jeopardy with no real promise of a return to pre-pandemic giving levels.”

A big one came in December 2022, when the Metropolitan Opera announced it would tap its $306 million endowment for a projected $30 million to make up for revenue shortfalls. Though few opera houses operate at the scale and expense of the Met, the company is still seen as an indicator of vital signs for the industry. The withdrawal was accompanied by a reduction in total performances, a commitment to better-selling contemporary works in forthcoming seasons and a widespread sinking feeling across the opera world.

And while a roughly 10 percent increase in attendance since last season and hinted hope of receiving a “transformative gift” is buoying some spirits, the New York Times reported in January that the Met is again tapping its piggy bank, drawing an additional $40 million in emergency funds (and leaving the endowment’s value around $255 million).

“It’s what keeps me up at night,” Gelb told the Times.

Within days, news from the Met collided with news from L.A., where the Los Angeles Opera announced it would scrap the world premiere of Mason Bates’s operatic adaptation of Michael Chabon’s “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay,” originally scheduled for the fall. (The work will receive its premiere with a student cast at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music before proceeding to the Met for the 2025-2026 season.)

“The audience is back and both earned and contributed revenue is stable,” L.A. Opera CEO Christopher Koelsch told the Associated Press. “The big difference is the cost structure is not pre-covid.”

Talk to the average opera fan about why this is happening and you’ll get thrown a familiar smelling bouquet of theories: Contemporary opera is terrible! Stop messing with the classics! Something about the young people!

But the ongoing crisis in opera parallels a current “free fall” (as Post critic Peter Marks put it) in American theater — with low ticket sales, slumping philanthropy and rising costs putting experimental platforms and long-standing institutions alike on indefinite hiatus or permanent leave.

“I like to step back and remember it’s a 400-year-old art form,” Washington National Opera general director Timothy O’Leary said in a phone interview. O’Leary has been in the opera business for 27 years, a career that has required weathering the dot-com boom, the 2008 financial crisis and the onset of the pandemic (he started at WNO in 2018). But he’s convinced opera is an adaptable art form — not just potentially, but historically.

“My favorite example is Handel, who gave up writing opera in the 1740s because ticket sales were tanking and opera was done as a business in London,” he says. “He decided oratorio was the way to go. We’ve adapted many times before.”

O’Leary pointed to compounding failures of dated systems, such as subscription models for ticket sales — which, in striking contrast to the subscription services most popular with consumers, require firm and early commitments with little flexibility, i.e. you pay for given seats on certain dates for select performances. “Some of these structures are endemic to the art form,” he says, “and we can innovate around them.”

O’Leary has managed to grow the WNO’s endowment from $8.4 million in 2018 to nearly $15 million. As a matter of policy, every bequest and gift goes straight to the endowment, and the company’s unique relationship with the Kennedy Center — which relieves its cash flow worries — allows the funds to sit and grow.

More important (no less than “the key to the future” to O’Leary) is changing the cost structures of opera — itself something of an old technology — and making some light tweaks to supply and demand.

A slight reduction of total performances — from nine productions and 48 performances in the 2019-2020 season to seven productions and 33 performances this season — created effectively higher demand. Ticket sales for every performance since January 2023 have been in the range of 95 percent to fully sold-out. (That’s up from an average of 62 percent in the fall of 2022.) The trim has also encouraged early demand, leading to a trend-bucking 12 percent boost in subscribership.

Making savvy use of space has also played a part in the WNO’s comparative health — this means understanding which productions to put in the Opera House (grand-scale productions), which to stage in the Eisenhower (well-suited to comedies that require some intimacy) and when to experiment in the Terrace Theater. An increased investment in projection design has also facilitated productions that are lighter on physical staging but richer in cinematic storytelling.

O’Leary has also noticed a pronounced uptick in first-time buyers, an increase in audience diversity and a drop in the average attendee’s age — in 2009, it was 68; today, it’s 59. He’s optimistic about the potential for new donors (such as the out-of-town contributor who recently underwrote two years of WNO’s American Opera Initiative) as well as engaging a younger donor class among the D.C. emergent tech and entrepreneurial sector.

“There isn’t going to be a magic bullet,” O’Leary says. “There is a major generational change that is forthcoming, and it’s up to us as innovators and artists to make sure the new generations see the value in what we’re doing.”

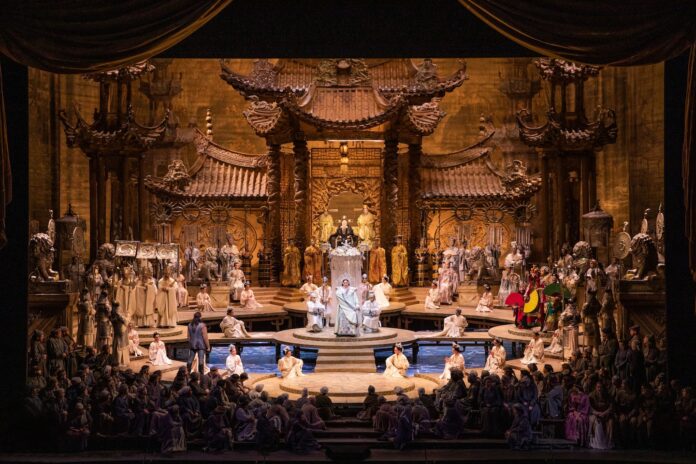

And, of course, there’s the opera itself. Earlier this week, the WNO announced the appointment of conductor Robert Spano as its new music director, and the company has high hopes for its spring productions of “Songbird” (a new adaptation of Jacques Offenbach’s “La Périchole”) and Puccini’s “Turandot.”

But while the relative health of a major company is an encouraging sign, opera as well as opera fans would be well served to check in on their regional opera offerings — and around here there are a lot: Virginia Opera just announced its 2024-2025 season; Opera Lafayette brings Mouret’s “Les Fêtes de Thalie” to town in May; the IN Series resumes its ongoing Monteverdi trilogy in May and June. It’s worth bookmarking such companies as Annapolis Opera, Maryland Opera and Opera Baltimore — and checking their schedules often.

For as much as opera companies can surgically cut and strategically innovate, the audience will have the biggest part to play in keeping American opera from reaching its final act. This may seem obvious, but here goes: If you’re an opera fan, go.