A Milei victory — which recent polls suggest is likely — will sound a death knell for a democracy recovered 40 years ago, after a century of fraudulent elections, political proscriptions and bloody military takeovers. But the menace doesn’t lie in Milei himself, even if a study found that his leadership style fits the authoritarian profile. He rejects basic democratic rules, denies any legitimacy to his political rivals, tolerates or promotes violence, and is ready to limit civil liberties, including that of the press.

In a country where social mood counts more than rickety institutions, the more serious threat to democracy is Milei’s supporters’ indifference to what he stands for. In polls and interviews, they have said over and over that they don’t care about his disdain for democracy, his outlandish and unworkable libertarian proposals, or his lack of basic knowledge of how to run a functioning state. They don’t care if this economist, comic and former footballer can really abolish the Argentine central bank and the national currency, as he says he will. Or that he wanted to eliminate subsidies for public education, health and other social services in the middle of a terrible crisis. Or that he has flirted with establishing a free market for human organs and firearms. Or that his obsession with his dead dog, with whom it’s said he communicates in the hereafter, and his violent, expletive-ridden outbursts when talking about the political establishment have sown doubts about his mental health. Local pundits deemed it a political achievement that he didn’t lose his temper or his mind during the presidential debates, as was widely expected.

In fact, Milei’s combustible personality is probably attracting more votes than his program, because his followers want him to get mad on their behalf. The Milei phenomenon is a protest scream. He is a human wrecking ball his voters want to hurl against the political system that has repeatedly failed them. It was by riding this radical discontent, by yelling insults and by wielding a chain saw with which he has promised to cut public spending (if not destroy the state itself) that Milei has gone from being a political nonentity to being the favorite in the runoff presidential election.

His rise is certainly the result of a spiraling economic crisis that has left more than 40 percent of the population under the poverty line and an inflation reaching 142.7 percent in a year. But he also represents the rejection of the political polarization that has engulfed the country for the past two decades. The current Peronist government, in power since 2019, and the opposing Juntos por el Cambio (JxC) that preceded it have been unable to offer any solutions to the nation’s problems, except for blaming them on each other. Facing Milei and his movement, they have reacted in character.

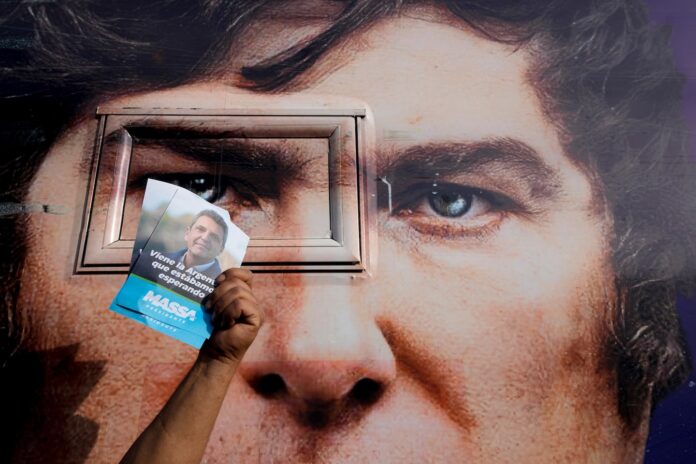

Massa has been doling out new subsidies and making promises about a rosy future. He is trying to pull off an act of political magic in which he is trying to make everybody forget that he is the most powerful figure in a failing government and the very person in charge of salvaging the ailing economy. Now he is Sergio Massa the candidate, the new guy who will end polarization and save the day.

Still, as the only alternative to Milei, Massa is not to be discounted. In the first round of elections, Massa surprised everybody, and especially the pollsters, by coming out on top with 36.78 percent of the vote against Milei’s 29.99 percent. (JxC obtained a meager 23.81 percent.) For a moment it seemed that, despite all the anger, the country had decided Milei was a bridge too far.

For their part, former president and JxC main leader Mauricio Macri and his failed presidential candidate Patricia Bullrich threw their weight behind Milei in the runoff. It cost them their coalition, after most of its other leaders refused to follow suit. It was yet another in a long line of historical cases — documented by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt in their book “How Democracies Die” — in which an established party opens the door of respectability to the insurgent authoritarian that goes on to subvert the democratic system.

Before Macri’s backing, Milei enjoyed the support of only the disaffected far right — people such as backers of former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, Tucker Carlson in the United States and Vox in Spain. After Macri’s endorsement, Sebastián Piñera (Chile), Felipe Calderón and Vicente Fox (Mexico), Iván Duque and Andrés Pastrana (Colombia), Mariano Rajoy (Spain), and Nobel Prize in Literature recipient Mario Vargas Llosa have all come on board, seeing Milei as a means to defeat Peronism in Argentina. (As part of this effort to make himself more respectable, Milei has moderated a few of his stances, no longer talking about eliminating social subsidies.)

“How far could the obsessive desire to defeat Peronism lead us?” Pablo Avelluto, former member of Macri’s cabinet, wrote. “Anything goes?” Avelluto abandoned Macri’s party for betraying its values by allying itself with Milei. Even still, he said he won’t vote for Massa: “I am indifferent to any of them winning.” He will leave his ballot empty.

Like him, so many in Argentina can’t reconcile the abstract ideal of democracy with its dismal reality. That indifference, that emptiness, is the true danger. For jumping into the void to escape miserable circumstances has rarely ended well.