“Well, I’ve always tended to dislike being told that something can’t be done,” Dr. Calne said in a New York Times interview years later. Dr. Calne, who died Jan. 6 at age 93, went on to revolutionize organ transplant surgery, pioneering the use of drugs and surgical techniques that gave hope to millions of people for whom organ failure had been a death sentence.

Along with another visionary surgeon, Thomas E. Starzl of the United States, he helped turn a risky experimental procedure into a widely accepted treatment, performing some of the first liver transplants and multi-organ transplantations even as colleagues hesitated to back his research.

“The reason I am here today, and the reason I am able to do my work, is because these two individuals went upstream,” said Srinath Chinnakotla, surgical director of the University of Minnesota’s liver transplant program. “They really were courageous to go against the paradigm then. If they didn’t take those risks, we wouldn’t have liver transplantation at all.”

When Dr. Calne began his transplant research in the 1950s, he faced two major problems. One was a matter of technique: How do you remove a faulty kidney or liver and then replace it with an organ that worked? The second was biological: How do you circumvent the body’s immune system, which rejects foreign tissue and treats it like an enemy invader?

Early efforts were far from promising. Dr. Calne operated on animals, mainly dogs and pigs, which died almost immediately. Animal rights activists who found out about the procedures sent him a bomb, he told the Times in 2012: “I was suspicious and phoned up the army — who blew it up.”

Dr. Calne tried stifling the dogs’ immune systems through radiation, which only made them sick. Then he turned to drugs, using an anti-leukemia agent called 6-mercaptopurine while performing kidney transplants in 1959. This time, one of the dogs lived for more than a month without the new organ being rejected. “It changed something that had been total failure to a partial success,” he said.

While Starzl developed surgical techniques in Colorado and then in Pittsburgh, Dr. Calne followed suit a continent away. In 1968, the year after Starzl performed the world’s first successful liver transplant, Dr. Calne undertook Europe’s first successful liver transplant while working as a surgery professor at the University of Cambridge.

By the mid-1970s, Dr. Calne was testing a new immunosuppressive drug, cyclosporine, championed by Jean-François Borel of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Sandoz. Dr. Calne led the first major study on its clinical uses, discovering that the drug increased the one-year survival rate for kidney transplant patients from 50 percent to 80 percent.

Cyclosporine became an essential part of organ transplant procedures — Starzl later discovered another effective immunosuppressant, FK-506 — and was credited with transforming attitudes toward a surgery that had previously been regarded, as Dr. Calne put it, “as an enterprise for mad surgeons ignorant of immunology, who really didn’t know what they were doing.”

“The discovery and use of cyclosporin made transplantation possible as a treatment to more and more people,” John Wallwork, a fellow transplant surgeon, said in a tribute. “Nearly 50 years on, it is still what is used for today’s transplant patients.”

Together, Dr. Calne and Wallwork performed the world’s first successful heart, lung and liver transplant on the same patient, a 35-year-old homemaker, in 1986. Eight years later, Dr. Calne led a team that undertook the first “cluster” transplant, replacing a patient’s stomach, small intestine, liver, pancreas and kidney.

Dr. Calne was knighted in 1986 for his contributions to medicine — in Britain, he was widely known as Sir Roy — and received a Lasker Award, considered medicine’s highest honor after the Nobel Prize, with Starzl in 2012. The surgeons were jointly presented with the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award for their work on liver transplantation.

The honor was flattering, Dr. Calne said at the time, although he tried to find satisfaction elsewhere. “I have a patient and it’s been 38 years since his transplant,” he told the Times. “He’s just come back from a 150-mile trek bicycling through the mountains. That’s my reward.”

The older of two sons, Roy Yorke Calne was born in the town of Richmond, now part of London, on Dec. 30, 1930. His father was a former engineer at the Rover car company, and his mother was a homemaker. His brother, Donald, became a Canadian neurologist and a leading expert on Parkinson’s disease.

After graduating from Lancing College in West Sussex, Dr. Calne enrolled at Guy’s Hospital Medical School in London at 16. He qualified as a doctor in 1952, according to a biography for the Lasker Award, and served as an army doctor in Southeast Asia for a few years before returning to England, where he was hired to teach anatomy at the University of Oxford.

While there, he attended a lecture by biologist Peter Medawar, a future Nobel laureate, who discussed the results of a successful skin graft between mice. The experiment suggested that the immune system could be manipulated, although Medawar insisted that there was “no clinical application whatsoever.”

Dr. Calne thought otherwise, asking himself, “Why couldn’t we do something like that with kidneys?”

He began working on kidney transplantation at the Royal Free Hospital in London and continued his research through a fellowship at Harvard’s Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, where the first successful kidney transplant had been performed on identical twins in 1954.

In 1965, he joined the University of Cambridge, where he was a professor of surgery until retiring in 1998. Dr. Calne continued to perform kidney transplants into his 70s and conducted medical research into his 80s, including on the use of gene therapy to treat diabetes.

His death, at a retirement home in Cambridge, was announced by the British Transplantation Society and the University of Cambridge, which did not give a cause. Survivors include his wife, the former Patricia “Patsy” Whelan, whom he married in 1956; six children, Deborah Chittenden, Sarah Nicholson and Richard, Russell, Jane and Suzie Calne; his brother; and 13 grandchildren.

Dr. Calne said that while he had no concerns about performing organ transplant surgeries for people in need (“If you come to me in pain and frightened, it’s my duty to help you”), he was wary that medical advances may have inadvertently contributed to overpopulation. In 1994, he published the book “Too Many People,” in which he argued that the world was becoming overcrowded and suggested that legal controls be placed on parenting, including the creation of a potential “permit to reproduce.”

Promoting the book, he told the Sunday Times of London that if he were starting a family today, he would stop at two children instead of six. And if his children wanted large families of their own, he added, “I would give them a copy of the book.”

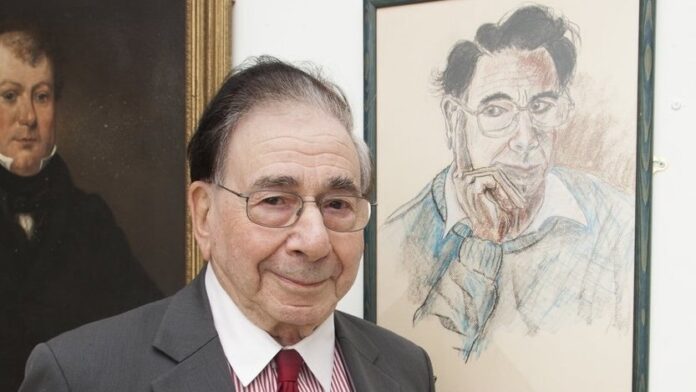

Between surgeries, Dr. Calne decompressed by playing squash and tennis. He also turned to painting, broadening his palette with encouragement from one of his former patients, Scottish artist John Bellany, who painted Dr. Calne for the National Portrait Gallery in London after turning to the surgeon for a liver transplant in 1988. Dr. Calne later painted many of his patients, with their permission, for canvases that decorated the walls of his home and office. Some of his pictures were exhibited at London’s Barbican Centre for a show titled “The Gift of Life.”

The portraits captured patients’ pain, journalist Laurence Marks wrote in a 1994 profile for the Independent, “but something else as well: the essence of his extraordinary partnership with them. He needs their stamina, their bravery and their trust. They need his knowledge, his candour and his humanity. Their haunted faces bring to mind those in paintings in the Imperial War Museum of soldiers coming out of the trenches.”