It was a bit frustrating for Ameen Beydoun when his first book about a young, African girl who immigrates to a new place wasn’t generating much interest in the form of book sales. He’d already course corrected from his original idea of pitching it as a children’s television show. He persevered, though, and it paid off. The second book in his self-published “Habibti Pada” series was named as a finalist in the Foreword INDIES Book of the Year awards, where it competed against more established independent publishers.

“Ultimately, I feel vindicated. I mean, I submitted the book to all of these established players — Fanatagraphics, Storm Kings Comics — you name it. I got rejected from them all, but I didn’t let that deter me,” he says. “Now, thanks to the INDIES awards, I’m competing against the very same publishers for Graphic Novel of the Year. Look out, y’all, I’m coming for the throne!”

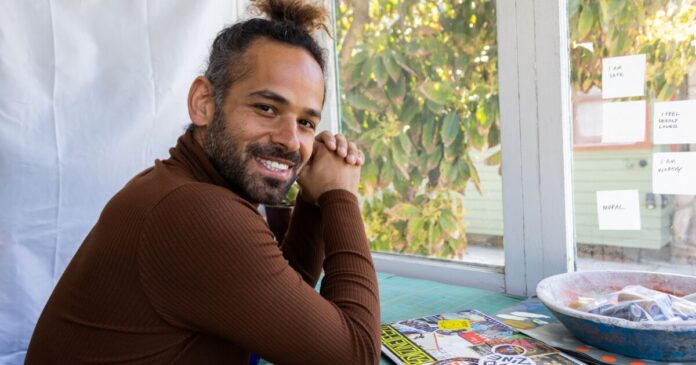

Beydoun, 34, is a writer and creator living in North Park. As a full-time author, he’s also working on getting his teaching certificate with a goal of teaching fifth-graders, while continuing to work on his series. He took some time to talk about wanting to tell a story about feeling like an outsider, the ways that his own experiences as a child of parents who immigrated from Lebanon both aligned and diverged with his protagonist, and soaking up all that San Diego has offered him since he’s arrived.

Q: What are your “Habibti Pada” books about?

A: The series follows a 10-year-old African immigrant as she navigates her scary, fantastical new home. Set in the Levant [Eastern Mediterranean region], the bulk of each issue is without dialogue: we hear Arabic, but (like Pada) we don’t have the luxury of subtitles. To make things worse, a single magical event breaks the realism in each episode — giant birds, ogre chefs, and ugly djinns threaten Pada and her new friends. Fear not! Across each episode, Pada hears a new Arabic word that will eventually help fight the monster in the story. Together, we build our vocabulary and understanding of this magical new world. “Habibti Pada” will appeal most to children interested in learning new languages, new cultures, and new mythologies.

Q: You’re the first-born of Lebanese-American parents who immigrated to New York City, where you grew up, but spent summers back in Lebanon with your extended family. After college at Wesleyan University, you joined the Peace Corps, working in Liberia and Comoros, and then working at businesses in Kenya and Senegal. What compelled you to first begin writing this series, especially coming from a background teaching and working in marketing and business development?

A: I remember sitting down and brainstorming what a project looked like. First, I wanted it to be engaging. I’ve seen a lot of rote memorization and lessons that put kids to sleep. I would rather have my readers engaged and learn next to nothing than bored and being force-fed “knowledge.” All of my creative work is driven by that philosophy, really: is it engaging? Anyhow, once the “Sesame Street” writer’s gig prompted me to write a pilot, I decided I had to do something with my Lebanese background, my lived-experience in East and West Africa, and something educational, as well. From that brainstorm, “Habibti Pada” was born.

What I love about North Park…

I have been enjoying skateboarding and biking around my immediate neighborhood. There’s just so much going on and the access to the outdoors — the sea, the desert — cannot be matched. Oh, and Mexico is right there so whenever you need a change of pace, it’s 20 minutes away!

Q: There are a couple of issues I think I’m picking up on in your books, but can you talk about what you wanted to address in each of your first two books, and the message you want to convey in this series, overall?

A: If you really want to understand any piece of entertainment, look at the villains, look at the monsters. They oftentimes tell us a lot more than heroes do, and they’re always more interesting anyway. I would say “Habibti Pada” is not too different. That’s not to disparage Pada; I love her, too, but if you want to understand what’s going on inside Pada, look at the monsters she’s projected onto her fantastic world.

In the first book, Pada is really out of her element. It’s the first day of school and for the new kids without friends, it’s scary enough. Now imagine being an immigrant and not understanding anyone around you. Pure terror. That’s what the monster in the first book is supposed to represent. In Arab mythology, the giant Anqa bird is said to be the most beautiful and most terrible creature in all of God’s creation. I took that monster and combined it with teachers I’d had, to make a giant school disciplinarian, but one that stomps and eats children. When you see the Anqa, you do not try to understand it, you do not try to engage with it — you just run. You do your best to survive and that’s what Pada has to do with Anqa and with her first day of school in a country where she does not understand anyone.

In the second book, Pada’s starting to understand this world. She now knows the games, she knows some of the kids, and it’s a much happier book in many ways. The monster in this book, al-ghouleh (which is where we get the word “ghoul” from) is scary for sure, but she speaks, she can communicate. Once Pada speaks to her, we find out she’s not actually all that scary. She’s mostly misunderstood, just like Pada. The message here is that in order to make the world less scary, you have to try and engage with it, you have to try and understand it.

The third book, which is coming soon, centers around the theme of environmental degradation, Syrian refugees, and how unchecked capitalism works to exacerbate both these crises. As such, the monster in the upcoming book is the most intelligent, the most complicated monster of all. Pada will really have to use her brain to overcome the many obstacles he sends her way.

Q: Why was it important to you to focus on conveying what it feels like to be an outsider, particularly an immigrant?

A: I’ll be the first to say that I have a very different experience from Pada. I am an outsider, but an outsider in a position of power. For example, when I was living in Liberia, I was a different color than everyone around me, just like Pada in Lebanon. Unlike Pada, I was a white person in Liberia, which afford me many more privileges than other foreigners and even more than some Liberians. In fact, I remember getting on a bus once and an old Liberian woman getting out of the coveted front seat so that I, a White man by Liberian standards, could take her place. Of course, I refused, but the story illustrates that being an outsider is not a singular experience. Pada’s experience of being an outsider in Lebanon is particularly difficult because being a Black person in Lebanon is especially difficult. Racism is a major issue in the country and while there are Lebanese people addressing these issues, it’s still not talked about nearly enough. In the first three books of the series, I don’t touch much on race in particular, but it’s the primary theme in the fourth and fifth books. Things are about to get a lot more complicated for Pada.

Q: What is the best advice you’ve ever received?

A: It’s a little cliché, but my brother recently sent me an article about a hospital chaplain who provides end-of-life care. In the article the chaplain said that at the end of people’s lives they talk almost exclusively about the relationships in their lives. Not money, not traveling, not being free or independent, but the human relationships in their lives. I took that to mean that we are defined by the relationships we create more than anything else. It’s been helpful to keep that in mind.

Q: What is one thing people would be surprised to find out about you?

A: I am very active. I surf, rock climb, spearfish, skateboard. My mom calls it CSS — Can’t Sit Still. I remind her that I got it from her.

Q: Describe your ideal San Diego weekend.

A: First, a dawn patrol surf session at Sunset Cliffs, scallop tacos at Mike’s Taco Club in Ocean Beach. Later, I’ll skateboard the entirety of Balboa Park (from north to south, of course!) and then take the bus home. Have dinner at Abay Ethiopian Market and Restaurant, followed by dancing all night at Whistlestop Bar. The next day, it’s spearfishing and snorkeling at Boomer Beach in La Jolla, bouldering in Santee, and dinner at Alforon Mediterranean/Lebanese restaurant on El Cajon Boulevard. Because every weekend should be a three-day weekend, I’d have street tacos in Tijuana, wine in Valle de Guadalupe, camping at Salsipuedes. All in Baja Norte, of course.