The first morning of September 2017 is remembered in San Francisco for two reasons: its record-breaking heat, uncommon to a city known for its fog-shrouded hills, and the acrid plume of smoke that spilled out the chimney of the Russian consulate, a century-old citadel that sits atop Pacific Heights.

A day earlier, the Trump administration had ordered the immediate closure of Russia’s consulate in San Francisco in response to Russian President Vladimir Putin expelling hundreds of American diplomats.

No one knows for certain what was burning at 2790 Green St. The San Francisco Fire Department did not immediately arrive on scene. As temperatures downtown climbed to a sweltering 106 degrees, the hottest ever recorded, ambulance calls more than doubled. Fifty people were hospitalized and three died. While overwhelmed city officials scrambled to meet the needs of the day, Cow Hollow residents, longtime neighbors to the consulate, quickly gathered in awe.

FILE: Black smoke billows from a chimney on top of the Russian consulate on Sept. 1, 2017, in San Francisco. In response to a Russian government demand for the United States to cut its diplomatic staff in Russia by 455, the Trump administration ordered the closure of three consular offices in San Francisco, New York and Washington.

Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesDiplomatic personnel were seen hauling boxes and other materials out of the building. Consulate staff coolly yet calmly rebuffed questions from journalists in the crowd. When the fire department finally did arrive, they were turned away.

It was a significant escalation in a diplomatic standoff, highlighting just how strained the relationship between the two countries had become. But the retaliatory bluster, while typical of the Trump presidency, was seen as inevitable in foreign policy circles, a consequence of a pattern of escalation that stretched back to the Obama era.

FILE : A staff member of the Consulate General of Russia carries boxes as the consulate readies itself for closure in San Francisco on Aug. 31, 2017.

Anadolu Agency/Getty ImagesThe U.S. State Department brushed it off, describing the move as merely bringing both countries’ diplomatic presences into “parity.” Yet, with smoke pouring out the chimney, it was hard to ignore the glaring question: What exactly were the Russians doing at 2790 Green St.?

Welcome to San Francisco

The first Russian consulate in the United States opened in San Francisco in 1852. It is Russia’s oldest and most established diplomatic branch in the country. A main “spy station,” according to former U.S. counterintelligence official Rick Smith, the Cow Hollow consulate housed only the most “experienced intelligence officers.” Those lucky enough to be operating here enjoyed million-dollar views of the Golden Gate Bridge and access to some of the biggest technological breakthroughs in American history, but they had to earn it. San Francisco, as Smith put it, “was never their first assignment.”

It’s easy to understand the city’s strategic benefits. After all, San Francisco is the financial center of the West Coast and has convenient access to the Pacific. In an article for Foreign Policy, Zach Dorfman highlights San Francisco’s “proximity to Silicon Valley, educational institutions such as Stanford and Berkeley, and a large number of nearby defense contractors — including two Energy Department-affiliated nuclear weapons laboratories” as being especially important to the Russians today.

Its history as a center of Russian espionage dates to the early days of the Soviet Union, beginning with one of the most notable figures in the consulate’s history: Grigory Kheifets.

A man of many titles, American officials knew Kheifets as the vice consul to the San Francisco office, but to his Soviet comrades he was nicknamed “Mr. Brown.” He claimed to have briefly served as secretary to Lenin’s wife before becoming lieutenant colonel of the Soviet intelligence service NKVD. It was during his tenure as vice consul when a mysterious pattern of espionage emerged in San Francisco.

A view of the Consulate-General of Russia building in San Francisco.

Nick Lobue

A view of the Consulate-General of Russia building in San Francisco.

Nick Lobue

A view of the Consulate-General of Russia building in San Francisco.

Nick Lobue

A view of the Consulate-General of Russia building in San Francisco.

Nick Lobue

Views of the Consulate General of Russia building in San Francisco. (Photos by Nick Lobue)

Law enforcement tasked with observing Russian activities often noticed men exiting and entering the consulate at odd hours, exchanging mysterious letters on park benches, but never addressing each other in conversation. In one instance in 1943, Alexander Igozor, an immigrant fleeing the Soviet Union, was abducted off Market Street in broad daylight. Six men with descriptions matching consulate staff were seen forcibly placing Igozor, screaming in resistance, on a boat back to Russia. Five years later, the New York Times reported that Igozor had “not been seen in San Francisco since.”

Courting Oppenheimer

Kheifets’ tactics were bold, and often focused on a singular goal: to help his country develop an atomic bomb. Known as an architect of Soviet nuclear espionage, Kheifets played a pivotal role in procuring American nuclear secrets. He was often reported courting professors and prominent scientists at elaborate dinners downtown. On more than one occasion, Kheifets tried and failed to establish relations with J. Robert Oppenheimer, the chief scientist of the Manhattan Project.

Oppenheimer derided any such contact with the Soviet officials as “treason,” though Kheifets and his team successfully managed to meet with some of his colleagues.

Martin Kamen, a promising young researcher at the radiation laboratories at UC Berkeley, was one of many unwitting victims in this intelligence campaign. After meeting Kheifets at a party, Kamen was approached for contacts at the radiation labs. Kheifets assured Kamen his interest in the growing field of nuclear research was well intentioned, and meant only for a comrade suffering from cancer and in need of experimental radiation treatment. When word of his meeting with Soviet intelligence broke out, Kamen was fired from his lab and blacklisted by the controversial House Un-American Activities Committee on accusations of spying. In 1951, the Chicago Tribune broke the news of his meeting with Kheifets, irreparably damaging his career.

FILE: Scene in the Caucus Room of the House Office Building as the House Un-American Activities Committee opened its investigation into alleged Communist activities.

Bettmann/Bettmann ArchiveKamen was one of many professors, artists, and intellectuals caught in the crossfire of anti-Communist sentiment in government and the media. After a failed suicide attempt and multiple libel lawsuits against the Tribune and other newspapers, Kamen cleared his name.

Despite the press attention and anti-Communist fervor in Washington, Soviet espionage continued throughout the 1940s. In a declassified report presented before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, intelligence officials noted that the San Francisco Consulate “was able to function as a spy center” that acted as home base for the “spy ring that delivered the A-bomb to the Soviets.”

The first closure of the San Francisco consulate

When chemistry teacher Oksana Kasenkina opened the third-floor window of the Russian consulate in New York, it wasn’t to get fresh air. For months she was morose, writing to Russian diplomatic offices and begging to return to her homeland. She was given room and board in New York while travel arrangements were being made, but grew increasingly paranoid. One morning in August of 1948, she took a deep breath and leapt from her window, miraculously surviving the three-story fall. According to the Los Angeles Times, while in critical condition at the hospital, Kasenkina told a friend, “I had to get out.”

American officials were in an uproar, accusing the Soviets of kidnapping Kasenkina, forging her letters and planning an elaborate cover story. The Soviets naturally denied any and all accusations. (It wasn’t until the Cold War ended that declassified reports concluded that Kasenkina suffered from a mental health crisis that most likely led to paranoid delusions.)

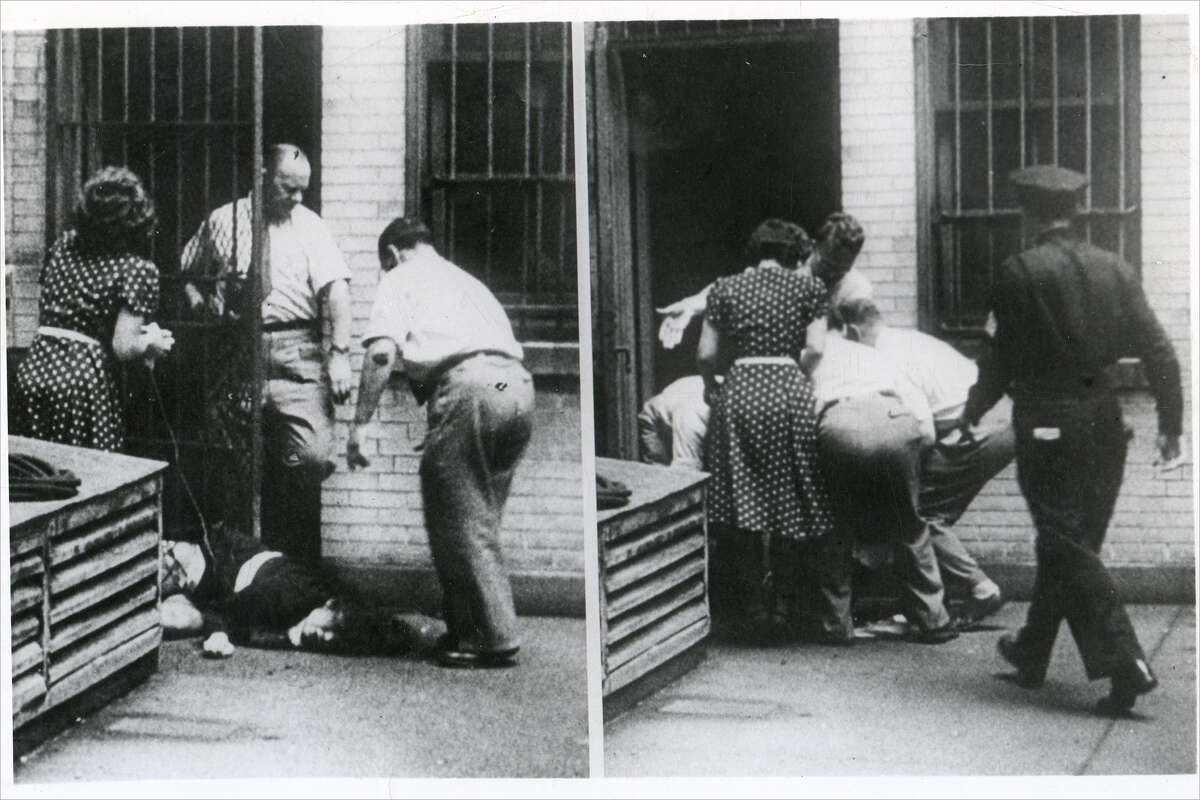

FILE: Oksana Kasenkina, a Soviet national, caused an international incident when she jumped from the third floor of the Soviet Embassy rather than be repatriated back to Russia, Aug. 12, 1948. In this photo, Kasenkina is being lifted and carried back into the consulate by embassy employees.

PhotoQuest/Getty ImagesAt the time, however, American officials were eager to prove their resistance to Communism by any means necessary. They ordered the immediate expulsion and the end to diplomatic immunity of the Consul General of New York. Weeks later, the Soviets responded in kind by closing all consulate branches in the country, including the main branch in San Francisco. It took less than a month for a decade of clandestine operations to end in a diplomatic standoff that eerily foreshadowed the 2017 closure.

A red carpet return

On June 23, 1973, the Soviet government returned to San Francisco, after a 25-year hiatus, to their new home: 2790 Green St. in the heart of Cow Hollow. A grand reopening was held, and invitations were sent out with an elegant gold emblem bearing the iconic hammer and sickle. An invitation is kept in a manila envelope in the San Francisco Public Library’s History Center, pristine amid a pile of yellowed newspaper clippings. The beauty of the letter’s design was deliberate, marking the weight of the occasion, and the extravagance of the venue.

The San Francisco Examiner called it a “true red carpet affair” with top Soviet leaders rubbing shoulders with “everyone who is anyone in the Bay Area” and drinking “Mumm and Moet champagne from France, Campari from Italy, White Horse Scotch from Scotland …” and the list goes on.

FILE: Plaque in front of the Russian Consulate building on Wednesday, Aug. 30, 2017, in San Francisco.

San Francisco Chronicle/Hearst N/San Francisco Chronicle via GettThe early 1970s were an important time for U.S.-Soviet relations. To cool tensions and avoid the risk of nuclear war, the U.S. began a policy of détente, gradually relaxing aggressive postures and creating more opportunities for diplomatic dialog between the two nations. The San Francisco Consulate’s reopening was a watershed moment in a more positive American-Soviet foreign policy. It was also a boon for Soviet spies.

The tech boom

That same decade, the tech sector began cementing its roots in the Bay Area. The personal computing revolution was just beginning in nearby Silicon Valley, and much like the decades before, Soviets now had a base of operations to acquire the most important technology for defense and economic edge. Smith, the retired FBI counterintelligence agent from San Francisco, told SFGATE that “most of the scope of espionage that Soviets were doing at that time focused on semiconductors, and anything cyber.”

American-made semiconductors — microchips that run computers, cellphones and most of modern life — were in high demand. Even today, tensions between the U.S. and its adversaries (like Russia and China) often hinge on the access to this precious technology. According to Smith, spies were known to pose as visiting students at Berkeley or Stanford. Their missions were to get close to those doing cutting-edge research and plan elaborate, yearslong heists of materials.

Surveillance cameras mounted on the outside of the Consulate General of Russia building in San Francisco.

Photos by Nick LobueSome heists were less elaborate. In 1981, the Wall Street Journal reported at least one instance where a Soviet spy marched off the street and into a Silicon Valley warehouse in broad daylight, taking components right off the inventory line. Thefts like these were estimated to cost upward of “$20 million a year.”

Later that year, UPI reported that 11 shell companies operated by two men “served as fronts for shipping semiconductors and other exotic materials to the Soviet Union” and by 1985, intelligence officials claimed that at least “35 percent of the personnel at the San Francisco consulate are electronic experts specifically engaged in high-tech espionage.”

Not in my backyard

American intelligence officials weren’t the only ones noticing Soviet activity. Large cables snaked in and out of the consulate roof. Neighbors often complained of radio and television interference. An Examiner article from 1978 described the penthouse as “a garden of disguised antennae” that fueled transmitters to “relay data to a Soviet satellite.”

On Christmas night in 1982, Cow Hollow residents were awakened by drilling and hammering. For two long nights, construction crews were seen hauling materials to the roof of the consulate, erecting a large penthouse that added at least another story to the already towering building.

FILE: A group of men gather on the roof of the Russian consulate in San Francisco, Calif.

San Francisco Chronicle/Hearst N/San Francisco Chronicle via GettIn classic San Francisco fashion, neighborhood organizations complained to the city building inspector, claiming the penthouse “blocks their view.” When an inspector arrived, he was politely barred from accessing the roof. For all intents and purposes, the consulate was Soviet property, and the city lacked jurisdiction. After a month, the penthouse was taken down due to a lack of proper permits, but the garden of cables, antennas and satellites remained in plain sight.

While the Soviets focused their efforts on the skies, the FBI concerned itself with operations on the ground, and at times below it. In 1983, former FBI agent David Castleberry claimed to have dug a tunnel with other FBI agents that led directly to the San Francisco consulate grounds. Wires strewn throughout the tunnel led to listening devices meant to monitor consulate communications. According to UPI, Soviet Consul Vladimir M. Kulagin said the reports of the tunnel constituted a “‘gross violation’ of international law.”

Smith, when asked whether Castleberry’s rumors were true, merely shrugged and gave a cryptic half smile, mumbling only, “That might have happened.”

A calm and then a storm

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the newly formed democratic Russian Federation inherited the consulate. The Russians continued espionage activities throughout the ’90s, but Smith conceded that the threat “wasn’t quite the same.”

The shared sense of purpose that drove Smith’s squad of young FBI recruits had all but vanished as the Soviet empire collapsed. It was a transitory and radical period in international relations. But it didn’t last. Once now-President Vladimir Putin gained power in 1999, the purpose returned with a new intensity.

A view of the Consulate-General of Russia building in San Francisco.

Photos by Nick LobueWhile Russian defectors and political opponents were being poisoned in cities across the world, Russian diplomats based in San Francisco began “showcasing inexplicable and bizarre behaviors” following Putin’s rise to power. San Francisco-based Russian diplomats who were being tracked by the State Department would go missing and turn up in seemingly random places.

Some diplomats would operate mysterious devices, often wandering directionless, conducting “weird, repetitive behaviors in gas stations in dusky, arid burgs off Interstate 5.” Just three months before the San Francisco consulate was forced to close, diplomats were seen “lingering where underground fiber-optic cables tend to run” according to a report in Politico. Unsurprisingly, these cables ran along strategic locations important for military communication. U.S. intelligence officials at the time provided one plausible theory: The Russians were likely gathering data to map out U.S. military capabilities in the event of a full-scale war. Yet, no one ever officially determined what the Russians were up to in San Francisco.

Closing time

As smoke spewed from the consulate’s chimney on that stifling September day, one could imagine the frenzied scene inside: bureaucrats scurrying across stately halls, hastily packing away classified documents, dumping anything incriminating in the fireplace. Their faces, sweating over the flames, betraying a mixture of resignation and defiance.

Today, Russia’s oldest and most established U.S. office is closed, and productive diplomatic conversations are rare. With war raging in Ukraine, the relationship between the United States and Putin’s Russia echoes an attitude of indignation not seen since the Cold War. Russia still formally owns 2790 Green St., but there are no stated plans to reopen the consulate in the future.

FILE: A woman walks passed the entrance to the Consulate-General of Russia building in San Francisco on Dec. 29, 2016.

Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty ImagesTo see 2790 Green St. now is to see a ghost. Soot stains the chimney from which smoke poured years ago. The paint is chipping, and cobwebs have formed along the high iron gate. The building still towers over the neighboring skyline, but its halls are silent. All that’s left to hear now is the hum of surveillance cameras fixed along the grand facade.

If you are in distress, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline 24 hours a day at 988, or visit 988lifeline.org for more resources.