In 1851, a gold prospector sat in a saloon in Nevada City, roughly 50 miles west of Lake Tahoe. He slowly began trading the newly acquired cash in his pocket for drink after drink, and before too long, despite being sworn to secrecy, he broke the vow he’d made just days before. The prospector told his fellow pint-swinging countrymen about the source of his newfound wealth: a source of gold in the hills just a few miles away.

As one would expect from any desperate gold rusher, they followed him home the next morning back to a tiny river in the Sierra foothills. However, his hopeful pursuers found no traces of gold near his supposed claim and deemed the effort — and the entire area — a humbug. In miner speak, a total bust. But today, it’s a bonanza — for anyone who likes to hike, that is.

That’s the supposed story of how the town of Humbug — and the nearby enormous mine that would eventually yield more than $3 million in gold — came to be in an otherwise nondescript section of what’s now Tahoe National Forest.

Today, the park is Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park. “Diggins” was the parlance of the time for any mine site, while the “Malakoff” moniker came from the town’s early French settlers, who named it for their country’s victory at the 1855 Battle of Malakoff. It’s one of the least-visited state parks in California, despite a few compelling reasons to visit. It’s home to a near-complete gold rush ghost town, a packed mining museum, and 20 miles of hiking trails that pass everything from a historic cemetery and schoolhouse to the “diggins” itself: a 7,000-foot-long pit more than 600 feet deep that led to America’s first-ever environmental law.

The destructive cost of gold

View of hydraulic mining at Malakoff Diggins by the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company in Nevada County; a miner is standing by a large monitor spraying water, 1874.

Carleton E. Watkins/California State LibraryFor prospectors, Humbug had its pros and cons. The pro was that there was indeed “gold in them thar” hills — and plenty of it, at that. The downside was that getting to it was extremely labor-intensive. Instead of being in a gold vein — or, better yet, in sizable nuggets like those in nearby Virginia City, Nevada — Humbug’s gold was embedded in rock and gravel, in tiny pieces and flakes that couldn’t be sorted or separated by hand or sieve.

Instead, miners expanded on the concept of a sluice box, which used water to separate tiny flakes of gold from dirt. But the scale of the hillside around Humbug required a supersize system. So miners began a new method of removing gold from the hills: hydraulic mining. Miners used high-pressure hoses to blast roughly 1 million gallons of water per hour at the hillsides. The force sent water, rock, dirt and anything else in the earth funneling into a supersize sluice: a water-filled, angled box that separated heavier gold from lighter debris like dirt and rocks.

The town became rich. It had 2,000 residents at its peak, and the world’s first long-distance telephone line ran through the town. Electric lights were installed. The name “Humbug” became not so fitting, and it was changed to “Bloomfield” in 1858 (and later “North Bloomfield,” when residents got word that a town of Bloomfield already existed in California). The town had several hotels and breweries, stores and restaurants, a school, a post office, and everything else a wealthy California mining town would have in the 1860 and 1870s.

The preserved interior of one of the many still-standing buildings in the park’s historic Humbug townsite.

Brian Baer/California State ParksUnfortunately, everyone else in Northern California felt the impact of blasting 25 million gallons of water per day at the hillside. Hydraulic mining sent hundreds of cubic tons of rocks, gravel and earth crashing into the Yuba River, which flows to the Sacramento River and eventually San Francisco Bay. Records estimate that the roughly 1 billion tons of debris released from the mine raised the bottom of San Francisco Bay by 3 feet and the Sacramento River by 16 feet, flooding farms and killing livestock, eroding private land, and delaying commerce along the all-important transcontinental railroad.

In 1882, a nearby landowner filed a lawsuit against the mine. And in 1884, the decision came down on Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company: Companies would no longer be allowed to dump any leftover materials — or “tailings” — caused by mining into rivers in the Sierra Nevada. It was the first pro-environment court ruling in the U.S. and effectively shut down the Malakoff mine, as well as all future hydraulic mining operations to come.

The ramifications were immediate. “From Dutch Flat to Red Dog,” wrote the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in a report on the ruling, “unemployed miners walked aimlessly about muddy streets muttering to hotel owners and shopkeepers whose consternation matched their own.” The mine shut down, the saloons closed, and some houses were dismantled for lumber during World War I.

Aside from a brief uptick during the Great Depression when struggling families moved into the town’s empty homes, the town’s population fell to fewer than 20 stragglers by the 1950s. It became a state park in 1965.

Hike through a ghost town and an underground mining tunnel

Malakoff Diggins, looking east. Shows pressure pipes and water from monitors.between 1869 and 1871

Carleton E. Watkins/California State Library

The current-day view of the former mine site at Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park

Suzie Dundas/SFGate

Malakoff Diggins mine, looking east, between 1867 and 1869; and the current-day remains of the diggins site. Photos: Carleton E. Watkins/California State Library, Suzie Dundas/SFGATE

Because the town of North Bloomfield became a state park soon after its abandonment, most buildings have been maintained, or at least occasionally repaired since their inception. The result is a protected 3,000-acre site with several excellent hikes through the ghost town and abandoned mine site, made all the more excellent by their relative lack of crowds and gentle elevation gain.

From the historic townsite, it’s a no-brainer to make the quick hike to the Marten Ranch (less than 1.5 miles round-trip). You can also park at the trailhead and cut off the .2-mile hike each way from the townsite. Not much is known about the still-standing homestead, including whether it had anything to do with the actual diggins. There’s very little elevation gain, as well as very little foot traffic, so it’s not unheard of to see black bears along this trail. Act accordingly.

However, for most people willing to make the rather windy drive to the park, the main draw is the actual mine site. There are multiple ways to reach it, including through the mine’s original Hiller drainage tunnel. It’s a mile-long tunnel tall enough to walk through and connects the parking area directly to the mine. If you choose this route, expect to trudge through knee-deep water and across large, slippery rocks in pitch-black conditions. You’ll need your hands free to hike, so cellphone flashlights won’t cut it — wear a headlamp.

The entrance to the Hiller Tunnel.

Suzie Dundas/SFGate

The Hiller Tunnel is a 1-mile walk to an abandoned gold mine in Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park.

Suzie Dundas/SFGate

Views of the entrance to the park’s Hiller Tunnel Trail. Photos: Suzie Dundas/SFGATE

Visitors who prefer to stay above ground should take the park’s easier Diggins Loop (2.6 miles, 200-foot elevation gain). The trail encircles the mine site, now resembling a massive canyon, and offers the chance to see multiple layers of rock in the exposed hillside. This area is prone to erosion and rockslides, so the lowest parts of the mine have filled it with soil and vegetation. It now looks more like a grassy plateau than anything else, belying the grand-scale environmental disaster it once was.

Combining the park’s Rim Trail and Slaughterhouse Trail Loop into one 5.5-mile loop will also reach the mine, passing the town’s original cemetery, church and schoolhouse on the way.

None of the state park’s trails are particularly well-trodden, so be prepared for overgrown plants and carry a map to help with basic route finding. Tall socks are a good idea.

80% of the ghost town’s gold remains

The still-standing Marten Ranch home.

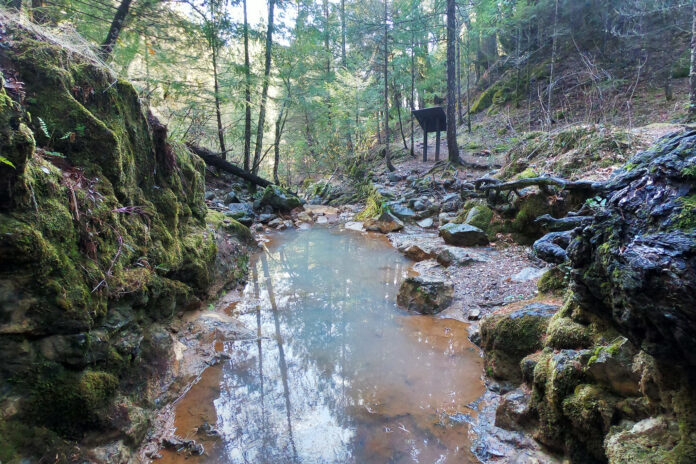

Suzie Dundas/SFGATEWhile it’s a long drive to visit the park and not explore the surrounding landscape — it’s a roughly three-hour drive from SF and two hours from Lake Tahoe — Malakoff Diggins does have one other big draw: the chance to strike it rich yourself. Visit at 3 p.m. on a summer Saturday, and you can learn the basics of gold panning from the park’s free classes at the ghost town’s Humbug Creek. Visitors can also bring their own gold pans or borrow one from the park visitor center to use on their own in the creek bed. And visitors committed to finding the next big bonanza will be happy to know sites at the park’s Chute Hill Campground are both reservable online and typically available last-minute.

The park’s museum and visitor center is staffed daily between Memorial Day and Labor Day and on weekends during the rest of the year. There’s a reasonable $10 parking fee that drops to $5 from September to May, and free walking tours of the ghost town are offered every day at 1:30 p.m.